Carol Leigh, Who Sought a New View of Prostitution, Dies at 71

Carol Leigh, who sought to change the image and treatment of sex workers — a term she is generally credited with coining — through both mainstream advocacy work and her colorful performances and writings under the name Scarlot Harlot, died on Wednesday at her home in San Francisco. She was 71.

Kate Marquez, her executor, said the cause was cancer.

Ms. Leigh (pronounced “lee”) began working as a prostitute after moving to San Francisco from the East Coast in 1978. In a 1996 interview with The San Francisco Examiner, she said she was galvanized into activism in 1979 after two men raped her at the sex studio where she worked and she realized that if she reported the crime, the establishment would be shut down, leaving her and other women there unemployed.

“I became very, very dedicated to changing conditions so that other women would not have to deal with what I dealt with,” she said.

At the time, prostitution was rarely thought of as anything but a crime, and men and women who sold sex were viewed as criminals and, often, as people who had been forced into the work by traffickers or circumstances.

Ms. Leigh was among a group of advocates who proposed a different view, one captured in the slogan that the movement adopted: “Sex work is work.” She argued that some people engaged in prostitution by choice, and that many sex-for-money transactions — the escort business, for instance — were not the street-corner deals the general public pictured.

Her point, sometimes expressed humorously, was to encourage a rethinking of the possible relationships between sex and commerce.

“There are so many women who make a living in the sex business and who don’t admit it,” she told The Arizona Daily Star in 1985. “Topless dancers are sex workers, for example. And we’ve all heard the story about the wife who has sex with her husband to get a new refrigerator.”

Ms. Leigh took credit for introducing the term “sex work” as an alternative way to describe the business of prostitutes and others. In “Inventing Sex Work,” an essay she contributed to the collection “Whores and Other Feminists” (1997, edited by Jill Nagle), Ms. Leigh recalled a conference organized by Women Against Violence in Pornography and Media that she attended in San Francisco in the late 1970s or early ’80s. The title of a workshop involving prostitution, she said, used the term “sex use industry.”

“The words stuck out and embarrassed me,” she wrote. “How could I sit amid other women as a political equal when I was being objectified like that, described only as something used, obscuring my role as an actor and agent in this transaction?

“At the beginning of the workshop,” she continued, “I suggested that the title of the workshop should be ‘Sex Work Industry,’ because that described what women did.”

Now the phrase is in common use, and it has been credited with helping to reframe the continuing debates on the subject.

“Carol Leigh was — and will always remain — a staple in the movement for sex workers’ rights,” Jenny Heineman, who teaches sociology and anthropology at the University of Nebraska Omaha and has written about sex work and feminism, said by email. “Never shying away from hard conversations, she coined the term ‘sex work’ to encapsulate the intersecting challenges that stigmatized and criminalized laborers across the globe face.”

Ms. Leigh was born on Jan. 11, 1951, in Queens. She described her parents as “disenchanted ex-socialists.”

“I was raised on discouraging tales of the failure of political struggles,” she wrote in “Inventing Sex Work.”

In the early 1970s she discovered feminist authors like Betty Friedan and Kate Millet. According to the 1996 profile in The Examiner, she earned a bachelor’s degree at Empire State College in 1974. She then studied creative writing at Boston University and founded a women’s writing group where feminist ideas were discussed and debated.

“By 1978 I had had enough of Boston’s mean and repressive atmosphere,” she wrote; she moved to San Francisco, where she hoped to explore a life in the arts.

“My friends who were artists were working in restaurants,” she told The Examiner. “I looked at them and I thought, I don’t want to work in restaurants. I’m an artist, I want to explore life. So for me, initially, prostitution was an investigation. I was also poor and feeling desperate at the time.”

The further she got into the life of prostitution, the more she felt a disconnect between her experiences and the feminist doctrines she had espoused earlier.

“Feminist analysis of prostitution as the ultimate state of women’s oppression didn’t fit the strength and attitudes expressed by the diverse women I met,” she wrote.

“Many lesbians were ‘out’ as lesbians,” she added, “but where was the prostitute in this new woman we had been inventing? She was degraded and objectified anew by the feminist rhetoric.”

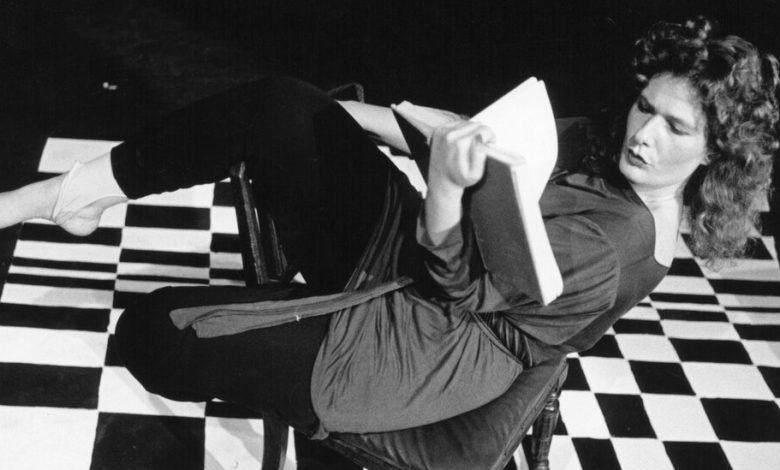

In the early 1980s Ms. Leigh developed a one-woman show, “The Adventures of Scarlot Harlot,” which she performed in San Francisco and elsewhere. In it she told stories from her working life, argued for a place at the feminist table and suggested that sex for money was perhaps not that different from whatever the audience did for money.

She also sold her own brand of perfume, Whore Magic, and other novelties. When she spoke at events, she would sometimes hand out colorful stickers that read “Whore Power” or “Be Nice to Prostitutes.”

But she was serious about decriminalization, health care, needle exchanges, reducing the prison population, how AIDS should be dealt with and other sex-work issues, and she was taken seriously. In the mid-1990s she served on a commission on prostitution created by the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, and in 2008 she was among the more vocal advocates of Proposition K in San Francisco, a ballot measure that would have had the effect of decriminalizing prostitution in the city. It failed. Its opponents included the city’s district attorney at the time, Kamala Harris.

Ms. Leigh is survived by a brother, Phillip.

Ms. Leigh made videos, organized art shows by sex workers, and in 2003 published “Unrepentant Whore: The Collected Work of Scarlot Harlot.” In the 1996 interview, she offered a succinct take on sex and decriminalization.

“This,” she said, “is the only activity that you can do for free but you can’t get paid for.”