The 17th-Century Heretic We Could Really Use Now

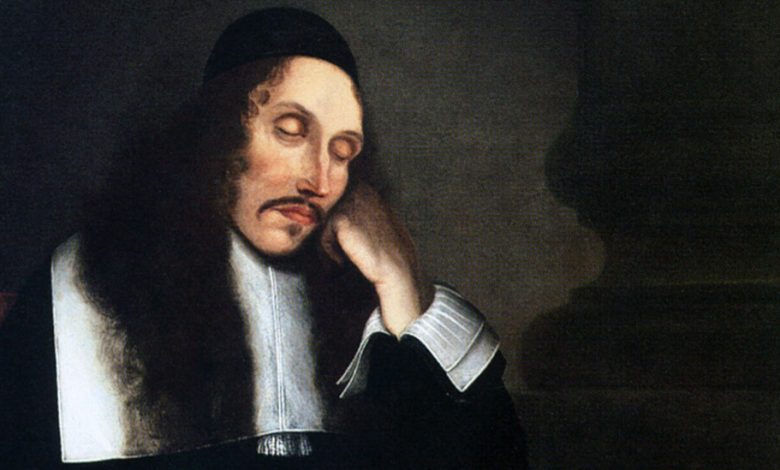

The Enlightenment philosopher Baruch Spinoza almost died for his ideals one day in 1672.

Spinoza, a Sephardic Jew born in Amsterdam in 1632, was a passionate and outspoken defender of freedom, tolerance and moderation. And so when Johan de Witt, the great liberal statesman of the Dutch Republic, whose political motto was “true freedom,” was lynched and mutilated by a mob whipped into a frenzy by reactionary rabble-rousers tacitly backed by orthodox Calvinist clerics, Spinoza wanted to rush onto the scene and place a sign that read (in Latin): “The lowest of barbarians.” If his landlord hadn’t held him back, the gentle philosopher would surely have been lynched himself.

Spinoza suffered much for his lifelong dedication to the freedom of thought and expression. His view that God did not create the world, and his disbelief in miracles and the immortality of the soul so enraged the rabbis of his Sephardic synagogue in Amsterdam that he was banished from the Jewish community for life at the age of 23. Only one of his books, about the French philosopher Descartes, could be published under his own name during his lifetime. His other works, arguing against religious superstition and clerical authority, and for intellectual and political liberty, were considered so inflammatory that his authorship had to be disguised.

There were other great thinkers in the 17th century, such as Thomas Hobbes and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, who prepared the ground for the Enlightenment of the 18th century. But few still appeal as to our imagination as Spinoza does. Living now as we do in a time of book-banning, intellectual intolerance, religious bigotry and populist demagoguery, his radical advocacy of freedom still seems fresh and urgent.

This is perhaps why new books about him are coming out all the time, including Jonathan Israel’s 2023 magnum opus “Spinoza, Life and Legacy” and even a best-selling French novel, “Le Problème Spinoza,” by Irvin Yalom. And all that for a philosopher who was denounced by Christians and Jews as the devil’s disciple long after his own time. Spinoza’s idea that God was not a thinking or creative being but nature itself was considered so scandalous that George Eliot, the British novelist who translated Spinoza’s “Ethics” in the 1850s, still insisted that her name not be mentioned in connection with the thinker she unreservedly admired.

Spinoza was convinced that all people, regardless of their religious or cultural background, were imbued with the capacity to reason and that we should seek the truth about ourselves and the world we live in. He insisted that our rational faculties could provide us with not only more precise knowledge, but with a path toward a happier life and better politics. In an essay called “On the Correction of the Understanding,” he wrote: “True philosophy is the discovery of the ‘true good’, and without knowledge of the true good human happiness is impossible.” That true good, in Spinoza’s view, can only be found through reason and not through religion, tribal feelings or authoritarianism.

Unlike Thomas Hobbes, who believed that only an absolute monarch could keep man’s violent impulses in check, Spinoza was an early proponent of a democratic ideal and representative government. But a free republic could only survive under a government of reasonable men who knew how to cope with conflicting interests rationally. As Spinoza put it, perhaps a little too optimistically, in his “Theoretical-Political Treatise”: “To look out for their own interests and retain their sovereignty, it is incumbent on them most of all to consult the common good, and to direct everything according to the dictate of reason.”