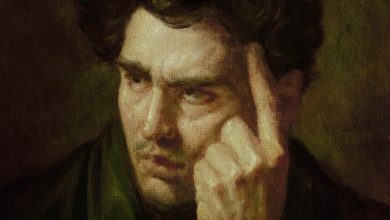

Banana Yoshimoto Wants You to Feel Again

DEAD-END MEMORIES: Stories, by Banana Yoshimoto, translated by Asa Yoneda

The five stories in Banana Yoshimoto’s collection “Dead-End Memories” — first published in Japan in 2003, it is her 11th book to be translated into English — are strange, melancholy and beautiful. At the center of each is a woman negotiating the quiet fallout of personal history.

In “House of Ghosts,” a young woman encounters, well, ghosts of an elderly couple in the soon-to-be-demolished apartment of her new lover. The ghosts go about their mundane lives, seemingly unaware that they are ghosts. They make the narrator “uneasy,” she says: “Ghosts probably lived in ghost time — time that flowed in its own strange way, somewhere completely removed from our own. Couldn’t mixing in it, even just a little, sap you of some of the vitality you needed to live in this world?” As the living couple’s intimacy deepens, the odd poignancy of the ghosts becomes entangled with their anxiety about the imminent destruction of the building, and with it their temporary relationship. After the narrator and her lover split, their paths meander as they age in a way that makes the reader smile. “This life seemed simple at first glance,” Yoshimoto writes, “when in fact it existed within a flow that was far bigger, as vast as the seven seas.”

In “Mama!” — one of the most brilliant stories I’ve ever read — Mimi, a publishing company employee, is poisoned by a disgruntled co-worker. Running beneath the long, slow current of her physical recovery is Mimi’s parallel spiritual transformation: “Those days — that dream — had exposed something inside of me and changed it. Just like a pet bird that had accidentally ventured out of its cage, the incident had cast me out of the world that I had known.”

The title story follows a credulous young woman who discovers that her fiancé has been cheating on her for months. On her quiet, often funny route to self-discovery she finds a companion in Nishiyama, a desirable bartender who works for her uncle. As they share close quarters, their friendship grows into something like love. “I knew that under our separate skies, Nishiyama and I were both so lonely it physically hurt,” she thinks toward the end of their time together. “And in my mind’s eye I saw once again the view from the upstairs window, and the quiet golden world where ginkgo leaves fell and settled forever on the ground.”

Two shorter entries move away from this warmth and tenderness and into an eerie disquiet. “Not Warm at All” takes the form of a recollection of a childhood friend who was murdered, and “Tomo-chan’s Happiness” follows a young woman trying to love after being raped at 16. Though there might be superficial similarities between the stories — about boyfriends, familial tensions, horrific incidents in the narrators’ pasts — each one feels distinct, rich in its own particular way.

Yoshimoto’s leading women are lonely and blinkered, though not in the way that I have come to expect from the prickly and elegantly severe fictions of writers like Rachel Cusk, Aysegul Savas or, lately, Jhumpa Lahiri, whose narrators tend to experience a failure or a lack of desire to integrate into society. Yoshimoto’s lonely women have more in common with the bachelor characters of, say, Bernard Malamud or Leonard Michaels or Haruki Murakami. They also resemble, in their awkward but striking agency, the characters of Alice Munro’s best short stories about young womanhood, by turns comedic, sad and aching for connection.

The spiky fictions of Anglophone literature of the past decade — staked on the idea of passivity as agency within a violent, dystopian, capitalist hellscape — are cutting and observant; but sometimes they leave the reader wondering: When can books be warm again? When can we have feelings again? Yoshimoto’s protagonists go out and act, they feel, they express, even if only to themselves. Even at their loneliest, these characters are a part of something, whether a relationship, a friendship, a family, a workplace, a society, a world.

These stories made me believe again that it was possible to write honestly, rigorously, morally, about the material reality of characters; to write toward human warmth as a reaffirmation of the bonds that tie us together. This is a supremely hopeful book, one that feels important because it shows that happiness, while not always easy, is still a subject worthy of art.

Brandon Taylor is the author, most recently, of “Filthy Animals.”

DEAD-END MEMORIES: Stories, by Banana Yoshimoto, translated by Asa Yoneda | 221 pp. | Counterpoint | $26