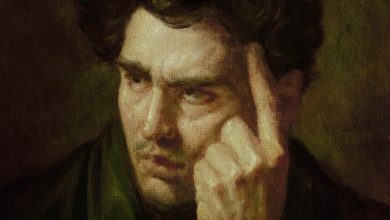

Gabino Iglesias, a Writer of Noir, Explores the Texas Underworld

AUSTIN, Tex. — At the dawn of the pandemic, Gabino Iglesias had already been living paycheck to paycheck in Texas for more than a decade. Then the public high school where he was teaching had devastating news: He was being let go.

Iglesias, a Puerto Rican novelist, found himself without a salary or health insurance. Unable to find other work in the bleak 2020 job market, he gambled on finishing the book he had started writing on his lunch breaks.

As Covid-19 raged outside, he wrote at a feverish pace for months on “The Devil Takes You Home,” his haunting noir thriller, which Mulholland Books will publish on Tuesday. Echoing the Book of Job, it follows a father in Austin who loses his job and health insurance, his young daughter to terrible disease and, finally, his marriage.

At wit’s end, the narrator, Mario, takes up an offer from a meth-addicted friend and embarks on a new line of work as a cartel hit man. This shift spawns a borderlands odyssey that blends noir and magical realism, meditations on religiosity and human cruelty, and social commentary on guns, the drug trade and resurgent racism.

“I put all my anger with the health care system into this book,” said Iglesias, 40, the author of “Zero Saints” and “Coyote Songs,” two novels which were critically acclaimed and enthusiastically received, albeit by relatively small numbers of readers.

In contrast, the arrival of Iglesias’s new book, with praise pouring in from noir masters, a book tour in the works and film rights already optioned, is shaping into a breakthrough moment for a writer who has long toiled just to make ends meet.

As American health care continues to confound and inflame, Iglesias is tapping into a source of familiar anguish. The book holds parallels to “Breaking Bad,” the series about a cancer-stricken high school teacher who descends into the meth underworld to secure his family’s future.

But unlike “Breaking Bad,” which won broad acclaim but faced criticism over the unconvincing ways some Latino characters were depicted, “The Devil Takes You Home” revels in the American West’s ethnic and linguistic diversity.

Some characters speak only English, perplexed by the Spanglish prevailing along much of the border. Others prefer the Spanish of the streets of Ciudad Juárez; grief-afflicted Mario effortlessly switches between English, Spanglish, Puerto Rican Spanish and varieties of Mexican Spanish.

Though contextual hints of meaning are ample, most of the book’s non-English dialogue is untranslated and unvarnished, reflecting how millions of people actually talk in Texas, whether in downtown El Paso or the grittier parts of Austin.

“I made it clear we’re not doing italics,” Iglesias said during an interview conducted in Spanglish at a bustling cafe in Austin, emphasizing his sense of relief when his editor at Mulholland, an imprint of Little, Brown, sided with him.

Growing into a writer who navigates languages and cultures wasn’t always in the cards for Iglesias. He was raised speaking only Spanish in Puerto Rico, the Caribbean island which is a United States territory (like many Puerto Ricans, Iglesias often prefers the word “colony”).

As a young reader, he was drawn to authors like Stephen King and Edgar Allan Poe, part of what he called a self-fed “very steady diet of horror.” He said he learned English partly by reading H.P. Lovecraft, dictionary in hand, looking up words he didn’t know.

In Puerto Rico, he was accepted into a marine biology program in college, then switched to get a business degree while working construction to pay the bills. Realizing the business world wasn’t for him, he then “wasted two years in law school,” began dabbling in journalism and got accepted into a postgraduate journalism program at the University of Texas in Austin.

Iglesias arrived in Texas with $236 to his name and got by without a car for two years. Scrambling to make ends meet on a stipend of about $930 a month, he taught radio reporting to college students, sold life insurance and taught English as a second language to Spanish-speaking immigrants.

That last experience, in addition to broadening his exposure to Spanish from Mexico and other countries in the Americas, reminded him of some advantages he held. Like his students, many of whom had crossed the border illegally from Mexico, he had followed his star to Texas.

But unlike them, Iglesias noted, he didn’t have to worry about immigration agents knocking on his door and deporting him at a time of resurgent xenophobia in the United States.

“Puerto Ricans may be second-class citizens but that American passport is extremely helpful,” he said. (Puerto Ricans have been United States citizens since 1917, but island residents cannot vote in presidential elections and lack voting representation in Congress.)

Still, Iglesias said he was frequently asked about his immigration status when looking for work, and as he sought out one low-paying office job after another, he was often greeted with indifference or skepticism from potential employers.

“My education and my CV don’t go hand in hand with what I look like,” he said. “When you’re a stocky brown guy with an accent, there’s not a lot of people clamoring to give you opportunities.”

Even after obtaining a Ph.D. in journalism, Iglesias said he still nurtured dreams outside of academia. More than once, as he pressed on with his own writing, he said colleagues suggested it would be a good marketing decision to change his name to “something with fewer vowels in it.”

Then there are the many sacrifices newly minted scholars make to secure tenured jobs. He saw contemporaries moving around the country from one college campus to another, churning out ultra-specialized work aimed at burnishing their professorial credentials.

“I didn’t want to spend my entire life writing articles for journals that no one’s going to read,” he said.

So he focused on his writing while also holding down various gigs, such as producing book reviews, grading papers and teaching online writing classes, to pay the bills.

It was enough, he said, to a keep a roof over his family, which includes his 9-year-old son, his wife and a rescue pit bull. They still live in low-income housing in Austin, even as Iglesias is finally finding broader recognition.

The results of his dedication to his craft are not for the faint of heart. He cited practitioners of Appalachian noir such as David Joy and S.A. Cosby as influences, and said the aim of his work was to “bring it down into the gutter.”

Some scenes in “The Devil Takes You Home” graphically explore how religious fervor can justify just about any course of action. In other stretches, he explores the blood-soaked hypocrisy of border security policies that allow guns trafficked from the United States to nurture Mexico’s drug trade.

Then there are the eerie scenes in the smuggling tunnels under the border, where the criaturas live, or the sense of surprise when in the presence of an exceptionally brutal drug lord who speaks with a theologian’s eloquence.

“Being in the presence of monsters is OK, as long as you don’t think too much about what they’re capable of,” Mario says. “The scarier thing is when you realize what you’re capable of yourself.”