Is the Human Impulse to Tell Stories Dangerous?

THE STORY PARADOX

How Our Love of Storytelling Builds Societies and Tears Them Down

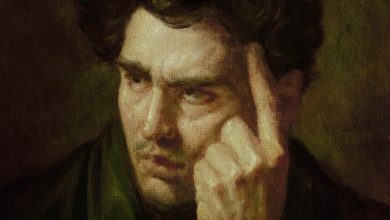

By Jonathan Gottschall

It is a “considerable bother,” says Jonathan Gottschall, to write a book; he lightens the task by writing about himself and excusing himself from extensive research. He sets a memorable scene of a morning spent in the lounge of a college psychology department flipping through the indexes of textbooks. He concludes from this that no one has ever undertaken his subject, the “science” of how stories work. Eureka.

Gottschall, a research fellow at Washington & Jefferson College, tells us that “for as long as there have been humans, we’ve been telling the same old stories, in the same old way, for the same old reasons.” We live in “unconscious obedience to the universal grammar” of stories. In other words: We don’t tell stories, they tell us. And everyone is the same kind of storyteller, Jesus and Socrates and all the rest. The universal story hard-wired into our brains is, says Gottschall, one in which everything gets worse until it gets better.

This “universal grammar” doesn’t seem to fit the Book of Genesis, Norse mythology, Greek mythology, the Analects, the Rigveda, “Hamlet,” “The Brothers Karamazov,” “Madame Bovary,” etc. But that is the least of Gottschall’s problems.

In “The Story Paradox,” he explains that stories filter what we should hear into what we want to hear. What might seem like innocent narrative tension can mean the rallying of one tribe against another. These are perfectly sensible points, made decades ago by Hannah Arendt. Yet in this book Gottschall tells just such a story about himself: a heroic scholar whose original insight challenges our preconceptions, leading a charge against an enemy tribe of terrifying left-wing academics. Defending this version, he ignores others who have made arguments very similar to his own, and dismisses whole disciplines and professions that offer counterarguments to his views. Gottschall demonstrates the power of stories by falling for his own.

Little is original in his analysis. His notion that stories tell us arose out of the structuralist anthropology of Claude Lévi-Strauss in the 1950s. Philosophers have been hard at work on story; that goes unacknowledged. Gottschall does mention history and journalism, but only to dismiss them as elements of our culture’s storytelling “machine.” In this bonfire of the humanities, Gottschall frees himself from knowing what novels say, disciplines demand or traditions offer. His portrayal of Jesus and Socrates as tellers of stories is exactly wrong. They spoke in questions, riddles and parables, meant to refresh minds and souls. That spirit of inquiry is absent here.

So is the principle of noncontradiction. When it suits him, Gottschall cites examples taken from the very disciplines that he has dismissed. Right after a pungent section characterizing history as the useless projection of the present upon the past, he cites a book of history, because it says what he wants it to say. Again and again he does what he thinks he is criticizing: treating as evidence what supports his story, and ignoring the rest.

Gottschall dismisses uncomfortable realities by claiming that others do so. Psychology may not have much to say about stories, but it does have a name for that move: “displacement.” The operative literary term would be irony. Gottschall cannot be expected to recognize that. Literary terms such as “irony” do what Gottschall claims that no one before him has done: They allow us to distance ourselves from our stories by cataloging their devices. This is unfamiliar territory for Gottschall. He promises a paradox in his title, but none is forthcoming. He does not know the difference between a metaphor and a simile. When bungling the details of the Holocaust (who needs history?), he treats the reader to grammatical errors.

In the best part of the book, Gottschall cites the work of Jaron Lanier to explain how social media algorithms reinforce our worst tendencies. Wrong though Gottschall might be about a “universal grammar” of stories, he is certainly right that social media encourages narratives where we feel innocent and find others to be inhuman. But he cannot draw the crucial conclusion that a story needs a human storyteller, since he needs all utterances from ancient Bible verses to digital metaverses to be “story” in the same sense. He accepts that novels make us empathetic (an argument pioneered by the historian Lynn Hunt). But he cannot bring himself to say that reading “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland” is better than falling down a social media rabbit hole.

Gottschall chooses quantity over quality, tabulating surveys about novels rather than reading them himself. He cannot quite see that what the internet creates is an endless psychological experiment and not a story. By allowing the tools of big data and psychology to guide him, Gottschall blinds himself to this essential point about our contemporary reading experience. He is not wrong that social media algorithms draw us into unreflective narcissism. What he misses is that it is precisely psychology and big data, his own allies, that supply the digital commercial and political weapons that trap us in stories where we are always on the good side. Gottschall warns us of such stories and rightly so. But in his analysis of their multiplication and intensification he has confused the villain with the hero. In conflating human storytelling with automated manipulation, he has gone over to the side of the machines, without realizing that he has done so.

Gottschall ignores the basic difference between believing a story and becoming a storyteller. When he tries his hand at fiction, we see the problem. He gives us a short scene that (to many readers, at least) will seem to be about a young woman trying to escape a menacing attacker. “I’m the god of her little world,” Gottschall writes, creepily, before assuring us, more creepily, that he is a benevolent god. The story will be different when not narrated from a place of complacent omnipotence, for example if it is told from the perspective of the woman. It will also be different if told as nonfiction.

Gottschall’s view about our nonfictional world is that “almost everything is getting better and few things are getting worse.” It is hard to see how he can judge the past against the present, given his dismissal of both history and journalism. He relies upon Steven Pinker’s “data” on the issue of violence, though there is no such thing. Pinker cited others; his peculiar choices are usefully examined in “The Darker Angels of Our Nature.” In the fields I know something about, Pinker cherry-picked with red-fingered fervor; his best numbers on modern death tolls come from a source so obviously ideological that I was ashamed to cite it in high school debate. Like Gottschall, Pinker is a friend of contradiction. He supported his story of progress in part by pointing to rising I.Q.s at a time when I.Q.s were in fact in decline. He began his book by noting that the modern welfare states are the most peaceful polities in history, and concluded it by embracing a libertarianism that would lead to their dissolution. Pinker was telling us a story; it is a story Gottschall likes, and thus it is ennobled as “data.”

The most important development in American storytelling, ignored by Gottschall, is the collapse of local news. Most of our country is a news desert. It is very difficult for people, lacking the essential facts about their own lives, to begin to tell their own stories. Investigative reporting is not, contra Gottschall, just a part of some generic narrative of negativity. It provides people with a basis for their civic existence. Millions of little stories defend against one big story. But the millions of little stories need foundations in institutions. Gottschall has nothing to say about what it would take for Americans to become agents in, and tellers of, their own stories. He wants us to listen to one another, no matter how nonsensical our stories might be, but has no idea how to make what we say more reasonable.

Part of Gottschall’s tale of himself is that his views will offend the powerful. Yet his own account of the world does nothing to challenge the status quo. He treats political conflict only as culture war, a view that is more than comfortable for those in power. His most feared enemy, he says, are left-wing colleagues; he portrays their thinking as entirely about culture. One would think, reading him, that left and right had nothing to do with economic equality and inequality, a subject Gottschall ignores.

Though he claims to have read “2,400 years of scholarship on Plato’s ‘Republic,’” Gottschall misses the famous point in Book IV about the city of the rich and the city of the poor. In a country where a few dozen families own as much wealth as half the population, the opportunities for storytelling are unevenly distributed. Gottschall has nothing to say about this. He believes that we live in a “representative democracy” in which the stories told by the powerful simply reflect our own stories. No need, then, to think about the Electoral College, campaign finance, gerrymandering, or the suppression and subversion of votes. Gottschall offers not a challenge to the powerful, but a pat on the back.

Gottschall confesses that he was “confused about this book,” and it is not hard to see why. If everything is story, then all we have is our own; and our own story makes us feel good, until the moment comes when it doesn’t. Gottschall visibly suffers in these pages as psychology becomes his personal tar pit. In the end, he flails in the direction of “facts” and “science,” terms he has already reduced to cliché by confusing them with common-sense nostrums. Even had he told us what he meant by “facts” and “science,” he gives no clue as to how our brains would escape their supposed hard-wiring for story and think in such terms.

In his last gasp, Gottschall invokes the Enlightenment. One of its mottoes was “dare to know.” Kant, who used that phrase, knew that the liberation from others’ stories begins with liberation from one’s own. Gottschall does the opposite: Drowning in his own story, he grabs us by the ankles. Voltaire’s Candide was miles ahead of Gottschall: Understanding stories means knowing when to laugh at them. This book is just sad.