Searching for the Past in Cameroon, Only to Find It Is Still Very Present

Patrice Nganang traveled for weeks in the countryside of western Cameroon in 2017, doing research for the final novel of his monumental trilogy about his country’s fraught history.

The book, “A Trail of Crab Tracks,” explores the birth of independent Cameroon in the 1960s and its subsequent descent into civil war. Nganang, 52, wanted to get the details just right, from the experience of guerrilla fighters in the jungle to the names of plants and local rivers.

“I was very careful,” Nganang said last month as a torrential spring rain fell outside his New Jersey home. “I didn’t want an older person to read it and say, ‘Come on, my son. It’s not right!’” His laughter, like a thunderclap, filled the room.

What he learned, he said, was that the past still shaped the present: Deep divisions sown in the colonial era persisted in the region and threatened to erupt into conflict.

Western Cameroon is English-speaking, and as he met with people there, he encountered growing opposition to the Francophone regime of Paul Biya, which has been entrenched in power since 1982. The tension was over autonomy as well as language, and had its roots in the country’s partition after independence.

“The government was declaring war and cracking down on Anglophone protests,” he says. “They hadn’t started killing yet.”

Now, he adds, “there are 20,000 people dead.”

Nganang wrote about what he witnessed and heard — and was detained at the airport in Yaoundé, the capital city, as he tried to leave the country. Held in a secret location for three weeks, Nganang feared for his life. He was also worried about his work in progress. “They kept my computer, with all my research. I thought, ‘Oh, no, now I’ve lost the novel!’” he says.“But luckily I didn’t.”

Finally released and expelled from the country, Nganang emerged with a deeper commitment to his overarching project: an examination of Cameroon’s national identity, and how it has held within it the seeds of both great promise and disappointment.

In the first novel of the trilogy, “Mount Pleasant,” published in the United States in 2016, Nganang brought to life Sultan Njoya’s Palace of Dreams, a magical court of artists and visionaries that fell prey to the colonial turf wars that carved up the country in the years leading to World War I. (Cameroon was claimed by Germany in the late 19th century, but in 1919 was divided into French and English territories by the League of Nations.) The second novel, “When the Plums Are Ripe,” followed in 2019 and celebrated the unsung Cameroonian soldiers who fought alongside the Allies in World War II.

“When you look at these three time periods and generations,” Nganang explains, “you realize each of them had a dream of Cameroon. Each of them also had a different map because the map of Cameroon changed all the time. So their dreams never matched, and it was ripe for conflict.

“The dream of Cameroon is contradictory,” he continues, “because on the one hand you have this violence and brutality and yet you also have this utopian idea: ‘Let’s dream big!’ That contradiction always inspired me, and I think it’s a reflection of the Cameroonian character, maybe the African character.”

As the second novel closes, the independence struggle is but a faint rumor and debates over Cameroon’s future arejustforming. These contentious views will take center stage in the final volume, “A Trail of Crab Tracks,” as an armed resistance movement fights for a unified vision of the country. The novel — written in French with a mix of pidgin and “Camflanglais” (urban slang or vernacular), and translated by Nganang’s longtime collaborator, Amy Baram Reid — brings the cycle to a dramatic close.

“The three novels are like a cake: tripartite,” Nganang says. “They are very much complex, but I also wanted them to be entertaining.”

Dense and immersive, “Crab Tracks” is also playful, irreverent — a novel of pogroms and resettlement camps but also fancy balls and scandalous affairs. “I always wanted to come back to ‘Madame Bovary’ and write a good novel about adultery,” he jokes.

The story lines in the book unfurl on two levels, shuttling crablike between Obama-era America and newly independent Cameroon. In the contemporary parts, the narrative centers on Tanou, a Cameroonian academic in New Jersey, and his widowed father, Nithap, whose visit is extended after an accident. Their relationship is one of quiet estrangement; both father and son harbor secret lives that have complicated their marriages. Nithap, as the reader gradually learns, spent several years among the rebels of western Cameroon, a chapter unknown to his son, which contained perhaps his greatest love.

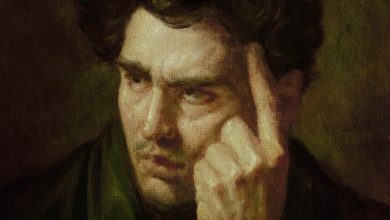

Yaoundé, Nganang’s hometown, is at the center of his work. “The world is my country, Cameroon is my subject, and Yaoundé my field of definition,” he said in the epitaph of his most recent book.Credit…Stacy Kranitz for The New York Times

The family story mirrors a national history of silences and betrayals: The two are inevitably, and tragically, linked. “The Cameroonian soul is a battlefield,” one character observes; another beseeches God to hear his “prayer of this bloodied land, of this family whose very heart was caught up in the pulsations of a country.” The story also reflects Nganang’s own maturity, he says.

“Families are complicated, and it is a novel I could never have written in my 20s,” he says. “I thought, ‘Let me write a novel that speaks to the age I am now.’”

Nganang, who is chair of Africana studies at Stony Brook University, borrowed from his own life for the novel — from the daily rituals of suburban America to the lyrical descriptions of his hometown, Yaoundé, his “mental landscape.” Yaoundé, indeed, provides an evocative leitmotif throughout the trilogy: Nganang lovingly explores the city, neighborhood by neighborhood, as some areas flourish and others sink into squalor over time. The epitaph to “When the Plums Are Ripe” makes his perspective clear: “The world is my country, Cameroon is my subject, and Yaoundé my field of definition.”

There is another overlap, too. The name “Tanou,” he says, means “father of history” or someone “who creates history as well as narrates it.” It happens to be one of Nganang’s many pet names. “Tanou” also refers to a cultural function, one that he has embraced on social media, as a self-proclaimed “Concierge of the Republic” (a nod, he says, to Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s sign-off, “Citizen of Geneva”).

“I would never have written this book if I hadn’t been on social media,” he says, describing the countless testimonials that Cameroonians around the world have shared with him, which have fueled his posts and informed his novel. “It changed me and changed the landscape of my writing because it made it possible for people to actually hear what I want to say.”

Social media has certainly given Nganang a significant platform from afar on the country’s issues, including the ongoing war with its English-speaking minority. “I’m a minority myself in Cameroon, a Bamileke,” says Nganang, who has also reported from conflict zones in Mali, Rwanda and Liberia. “All the writing I do, all the political positions I have, is through the lens of a minority position: How is it protected? How is it articulated? How does it cause conflict?”

So where does that leave Nganang, who is unable to return to Cameroon as long as Biya’s dictatorship remains? Nganang — true to the name “Tanou” — takes the long view.

“History is the backbone of everything we do, everything that happens,” he says. “Are things going to change? Like Yaoundé’s neighborhoods, what is poor today was rich yesterday and what is rich now was once poor. The reality of Cameroon, and Africa in general, is that nothing is forever.”