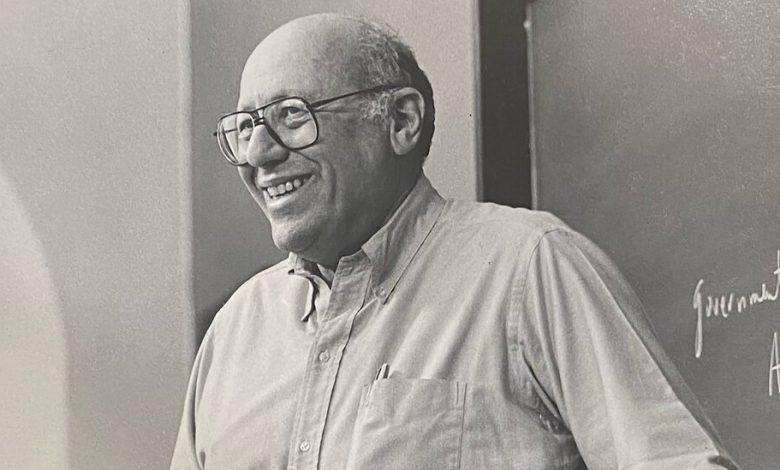

Albert Madansky Dies at 88; Gauged Risk of Unwitting Atomic War

Albert Madansky, a virtuoso statistician who sought to quantify the risks of accidental nuclear war and the value of stock options and publicly risked his reputation by rating which New York delicatessen served the best pastrami sandwich, died on Dec. 8 in Chicago. He was 88.

His death, in a hospital, was caused by heart failure, his daughter Michele Madansky said. He had been a professor at the University of Chicago’s Graduate School of business since 1974.

In 1958, in the thick of the Cold War, Dr. Madansky was a mathematician for the RAND Corporation, the research institute in Santa Monica, Calif., when he and Gerald J. Aronson collaborated with Fred Charles Iklé to study the risk of an unauthorized nuclear explosion.

The risk was “not negligible,” the study’s authors wrote, “but it is impossible to say how likely it is.” Sabotage, for instance, “does not lend itself to a statistical evaluation.”

But noting that any risk could have serious consequences, the report recommended what became known as Permissive Action Links, which required the installation of coded safety locks on nuclear weapons and missiles and the approval of a minimum of two individuals to launch a nuclear attack.

Upgraded versions of the Permissive Action Links system are still in use by the American military.

Among Dr. Madansky’s many books and publications was an article he wrote in 1979 with Gary L. Gastineau in which they cautioned against using computer simulations to predict the value of a stock option, which gives an investor, typically a company employee, the right to buy or sell a stock at an agreed-upon price and date.

“Simulations can typically answer the question, ‘Given the actual history of security prices, what return on investment would a given options strategy have produced?’” they wrote, in the Financial Analysts Journal. “But they cannot reveal whether a specific options strategy is good, bad or indifferent.”

Rather, they assessed investment strategy by comparing actual and implied stock price volatility.

Dr. Madansky put his expertise to work on an entirely different challenge in 1999. Responding to criticism that a list of the 100 best novels of the 20th century by the Modern Library, a division of Random House, included 59 Random House imprints, the Modern Library enlisted Dr. Madansky to make its nonfiction rankings more scientific.

Each book was rated numerically by a panel of judges drawn from Modern Library’s editorial board. After an initial vote on 900 titles, the list was pared to 300 and the panel voted again. Dr. Madansky then shrunk the list to 100 on the basis of each book’s numerical ranking. By that method, Random House imprints accounted for about one-fourth of the final list of 100 books. (The autobiographical “The Education of Henry Adams” topped the list.)

Albert Madansky was born on May 16, 1934, in Chicago to Hershl and Anna (Meidenberg) Madansky, Jewish refugees from Poland. His father was a shoemaker, his mother a seamstress.

Albert was always good in math but got no encouragement to pursue it — until a high school teacher more or less hoodwinked him into it. The teacher, Walter Burks, Dr. Madansky wrote in an unpublished memoir, “had a ‘breakfast club,’ a kind of detention where students who were unruly in class had to come to school for one half-hour before school started and sit in this room as punishment.”

“One day he decided to ‘invite’ me to his ‘breakfast club’ on some trumped up charge,” he wrote. “I discovered that his intent was to get me there early so that he could introduce me to calculus. I enjoyed that session, went to the public library, took out some books on calculus, started reading them and then voluntarily showed up at breakfast club for Mr. Burks’s tutoring.”

He earned all of his degrees from the University of Chicago: a bachelor’s in 1952, a Master of Science in 1955 and a doctorate in 1958.

Dr. Madansky was a mathematician for the RAND Corporation from 1957 until the early 1960s, when he became a fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford.

He also taught mathematics and econometrics at the University of California, Los Angeles, and marketing and econometrics at Yale.

He later served as a senior vice president of the Interpublic Group of Companies, a marketing conglomerate, and president of Dataplan Inc., both in New York City. He joined the City College of New York as a professor of computer science in 1970 and was named department chairman in 1971.

He returned to the University of Chicago as a faculty member in 1974 and served as associate dean and deputy dean from 1985 to 1993. He was named the H.G.B. Alexander Professor of Business Administration at the university’s Booth School of Business in 1996 and retired as professor emeritus in 1999.

He also served as director of the Centers for International Business and Education Research and editor in chief of its Journal of Business.

In 1956, he married Cara Yore; they divorced in 1986. In addition to their daughter Michele, Dr. Madansky is survived by his wife, Paula (Barkan) Madansky; three other children from his first marriage, Susan Groner, Cynthia Madansky, Noreen Ohcana; his stepchildren, Deborah Haizman, Rebecca Hirschfield and Jonathan Klawans; 13 grandchildren; and one great-grandson.

As the director of the University of Chicago’s Center for Management of Government and Nonprofit Enterprise, Dr. Madansky in 1975 was one of a number of prominent thinkers — among them Jane Jacobs, John Kenneth Galbraith, R. Buckminster Fuller and Milton Friedman — who were asked by The New York Times for suggestions for solving New York City’s fiscal crisis.

He asked whether the city government could squeeze more productivity from its work force rather than resorting to layoffs. New York offers so many services, he said, adding: “It’s always been understood that because New York gives these services to the community, then New York wants them, but the people might prefer to see a fiscally sound city.”

In 1976, in collaboration with Martin Shubik, an American economist, Dr. Madansky released what may have been his most controversial statistical conclusion: the results of a blind taste-test of pastrami and corned beef sandwiches delivered to an office on East 54th Street from four of Manhattan’s pre-eminent delis: the Stage, Carnegie, Gaiety-East and Deli-East. The Deli-East won.

Critics fulminated that the methodology was flawed — that, for starters, sandwiches eaten outside the mustardy milieu of a deli can never taste as good.

But Professor Shubik wrote that their research represented “a modest attempt to preserve for the annals, before it became too late, a record of the Great American Vanishing Species known as the Pastrami and the Corned Beef Sannawiches.”

In fact, all four of the delis closed their original locations.

Perhaps inspired by his earlier research into nuclear weapons, Dr. Madansky pointed out that Dr. Brown’s Cel-Ray soda was a vital ingredient for gastronomicalimplosion.

“Its catalytic action when combined with pastrami in the stomach is that of an atomic bomb,” Dr. Madansky wrote. “Varoom, and the pastrami disintegrates, is digested, and its heart-burning power is released in full.”