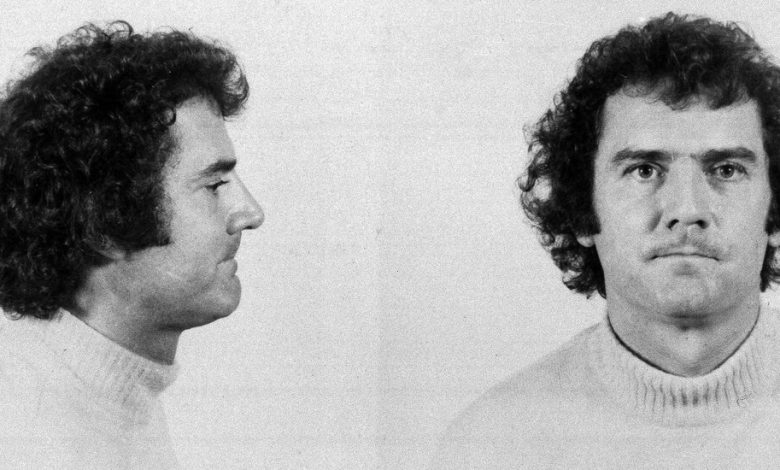

Frank Salemme, One-Time Head of the New England Mafia, Dies at 89

Frank Salemme, a Boston mobster who took over the New England mafia in the 1990s, then cooperated with prosecutors against two of his former allies when it emerged that they had been longtime F.B.I. informants, died on Dec. 13 at a federal medical facility in Springfield, Mo. He was 89 and had been serving a life sentence for his role in the 1993 murder of a Boston club owner.

An official with the Bureau of Prisons confirmed the death, at the United States Medical Center for Federal Prisoners, but said a cause had not been determined.

Known to his friends and the news media as Cadillac Frank, Mr. Salemme (pronounced sah-LEM-ee) was an energetic, dapper character in the Boston underworld. By his own admission he participated in eight mob hits during the Boston gang wars of the 1960s.

He largely sat out the 1970s and ’80s thanks to a 1973 conviction for attempting to murder a lawyer, John Fitzgerald, by planting a bomb in his car. Mr. Fitzgerald lost his right leg in the attack but survived, and Mr. Salemme was sentenced to 16 years in prison.

He got out in 1988 and joined the Patriarca crime family, the leading organization within the New England mafia, just as a generational transition was setting off a leadership struggle. He and another promising underboss, William Grasso, quickly became the real power behind the titular head of the family, Raymond Patriarca Jr.

On June 16, 1989, a team of hit men shot Mr. Salemme in the chest and leg as he was standing outside an International House of Pancakes in Saugus, a northern suburb of Boston. Four hours later, Mr. Grasso’s body was found floating in the Connecticut River.

Mr. Salemme survived and went into seclusion at his home in Sharon, Mass., south of Boston.

Over the next year, the federal authorities cracked down on the New England mob, indicting most of the members who might have challenged Mr. Salemme for control. By 1991 he was its de facto leader.

But he ruled over a declining empire. Law enforcement agencies had whittled down its membership and riddled its rank and file with informants, setting off reprisals within the organization. In 1993 a man named Steven DiSarro, who owned a nightclub in Boston, disappeared soon after he decided to cooperate with the government.

To shore up his dominion, Mr. Salemme tried to build an alliance with the Irish mafia, led by his longtime friends James (Whitey) Bulger and Mr. Bulger’s lieutenant, Steve Flemmi, known as the Rifleman.

That effort ended in 1995, when the federal authorities indicted the three men on racketeering and extortion charges; murder charges were added later. Mr. Salemme was convicted and sentenced to 11 years in prison.

Then, in 1999, his lawyers learned that Mr. Bulger and Mr. Flemmi had spent decades as deep informants for the F.B.I., handled by an agent named John Connolly. They had bribed Mr. Connolly, the authorities said, and fed him information about Mr. Salemme, including details that helped lead to his arrest in the Fitzgerald bombing.

Mr. Connolly in turn had tipped them off to the coming indictment. Mr. Flemmi was arrested, but Mr. Bulger went into hiding and was captured only in 2011.

Shocked at the betrayal by his friends, Mr. Salemme offered a deal: a reduction in his sentence in exchange for his testimony against his two former associates, as well as Mr. Connolly. He swore he was done with the mob, and apologized to the families of the men he had helped kill.

“You have my word now, that life is over,” he said in court. “The mafia has evolved into a street gang. I wouldn’t go back to any type of crime, let alone go back to the mafia.”

Mr. Flemmi and Mr. Bulger were sentenced to life in prison, while Mr. Connolly was sentenced to 40 years. Mr. Bulger was murdered in a West Virginia penitentiary in 2018. Mr. Connolly received a medical release in 2021, while Mr. Flemmi remains in prison.

Mr. Salemme entered the witness protection program in 2003, but left it a year later to live in the open in Boston. He was seen eating at the Busy Bee, his favorite restaurant in suburban Brookline, and even sat for an interview with a local reporter.

Francis Patrick Salemme was born on Aug. 18, 1933, in Weymouth, Mass., southeast of Boston, and grew up in the city’s Jamaica Plain neighborhood. His father, Romeo Salemme, was a ship painter, and his mother, Mary Agnes (Hagerty) Salemme, was a homemaker.

He served in the Army during the Korean War and, after receiving an honorable discharge, became a licensed electrician. By the late 1950s he was a low-level soldier in the Boston mob.

His son Frank Jr., himself well-known in Boston organized crime, died of leukemia in 1995. Information on survivors was not immediately available.

Mr. Salemme may have left his life of crime behind by the early 2000s, but the past can have a way of haunting old criminals. He was arrested in 2004 on charges of lying to investigators looking into the disappearance of Mr. DiSarro. He reached a deal and went back into witness protection, but in 2016 he was arrested once again.

Mr. DiSarro’s body had been found buried behind a mill in Providence, R.I., and Mr. Salemme’s old friend and nemesis, Mr. Flemmi, testified that he had witnessed Frank Jr. strangle Mr. DiSarro as Mr. Salemme looked on.

Mr. Salemme was convicted and sentenced to life in prison. By then he was 85 and in declining health. After several months in a federal prison in Brooklyn, he was transferred to the medical penitentiary in Missouri.

Although he insisted that he was innocent in Mr. DiSarro’s murder, at his trial Mr. Salemme seemed resigned to his fate. When the judge asked him if he had anything to say at his sentencing, he waved her off.

“Not really,” he said. “Anything I would have to say would be redundant. Let’s just wrap it up.”