William Greenberg Jr., Baker Who Sweetened Manhattan, Dies at 97

William Greenberg Jr., a baked goods impresario whose fanciful cakes, butter cookies, brownies, Linzer tarts and sticky buns would exert a Proustian hold over generations of New Yorkers, died on Feb. 7 at a rehabilitation facility in Valhalla, N.Y. He was 97.

His son Adam Greenberg announced the death.

Mr. Greenberg, an affable redhead at 6 feet 4 inches tall who was raised in the Five Towns area of Long Island, opened his first bakery in Manhattan in 1946, in a narrow storefront on East 95th Street, near Second Avenue, with $3,000 — poker winnings from games he played in the Army. It turned out that Mr. Greenberg was as skilled with cards as he was with a piping gun.

His bakery was a small space with a big name: William Greenberg Jr. Desserts, Inc. By 1971, he had expanded the company to encompass four modest locations, mostly on the Upper East Side, and employ 16 bakers. Mr. Greenberg no longer manned the ovens by then; he was the maestro in charge of the cake decorating, working mainly from what became his flagship, at 86th Street and Madison Avenue. He liked an audience as he wielded his frosting gun and often drew a crowd, including children, who would watch agape after school hoping for free samples.

They weren’t his only fans.

Lee Strasberg, the imperious director and acting teacher, loved Mr. Greenberg’s fudgy brownies; so, apparently, did the film director Mike Nichols, who was said to have coaxed his actors into their best work with the promise of one. The actress Glenn Close ordered themed cakes for wrap parties. A well-known decorator was said to have offered Mr. Greenberg’s schnecken (German for snail) — bite-size sticky buns — to his clients along with his bills, to soften the blow.

New York dynasties like the Lauders, the Tisches and the Roses marked special occasions with a Greenberg cake; for Jonathan Tisch’s 40th birthday, his mother ordered one shaped like the New York City skyline, the Tisch buildings highlighted with white frosting.

The writer Delia Ephron was partial to the chocolate cream tart — a cake, actually, layered with fudge and fresh whipped cream. Alexa Hampton, the interior designer, favored the candy cake, topped with shaved chocolate, crowned with rich chocolate squares and blanketed on the sides with vertical piping of whipped cream. Her father, Mark, was a schnecken man.

Another regular, Itzhak Perlman, a poker buddy of Mr. Greenberg’s, once ordered a cake fashioned in the shape of Ebbets Field, the storied home of the Brooklyn Dodgers, for his wife’s 40th birthday (not an easy creation, given the stadium’s elaborate Romanesque arches).

A Greenberg best seller for New Yorkers of all ages was the garage cake, sculpted to look like a garage outfitted with a fleet of chocolate cars. Yet Mr. Greenberg’s personal preference was for more impressionistic, abstract designs that evolved during a cake’s decoration as his muse beckoned.

One customer with a sweet tooth, Ida Serling, was so impressed by his work, she decided that he would be a good match for her daughter, Carol. Soon, she was sending Carol in alone to pick up her orders, hoping for sparks.

They married in 1955. Mr. Greenberg baked their wedding cake himself on the morning of the ceremony. It was a two-tiered yellow sponge affair layered with whipped cream laced with brandy, pecans and coffee extract, and latticed with white frosting. It was his favorite wedding cake recipe, he told The New Yorker in 1975. “It has an aristocratic air about it,” he said, adding, “I call it my Madison Avenue Victorian number.”

The New Yorker declared that Mr. Greenberg was to wedding cakes “what Henry Purcell was to wedding music or Edmund Spenser to the epithalamium” — that is, a wedding song or poem.

“He is an Old Master of the mixing bowl and the icing gun,” the magazine said, “an artist of the pale, shaded rose, the standup squiggle, the classic fluted edge, and the fine white line of frosting.”

Mr. Greenberg said simply, “Cakes are second nature to me.”

William Greenberg Jr. was born on Aug. 17, 1925, in Lawrence, N.Y., on Long Island, and grew up in nearby Cedarhurst. His mother, Miriam (Rosenbaum) Greenberg, was a dress designer and homemaker. William Sr. was in the furniture business.

William Jr. learned to bake from his aunt Gertrude — at least 10 of her recipes would become part of his bakery repertoire — and at 13 he started selling cookies to his classmates. He was soon baking for the Five Towns Woman’s Exchange and by 16 had hired his first employee, a classmate from home economics. He was making $300 a month selling schnecken, apple turnovers and cookies.

He was drafted into the Army in 1943 and sent to North Carolina State University to study engineering. He was then sent to Europe, where he volunteered for kitchen duty but ended up as a corpsman and a mess sergeant in Gen. George S. Patton’s army; he would forage for food once the troops had outpaced their supplies. He was among the first of the troops sent home after V-E Day, and it was while on a train from Germany to France that he racked up those $3,000 in poker winnings.

In addition to his son Adam, Mr. Greenberg is survived by another son, Seth, and four grandchildren. Carol Greenberg died in 2017.

The bakeries were a family business. Carol worked in sales and quality control, and the boys began working before their 10th birthdays, folding cake, pie and cookie boxes after school and on weekends at five boxes for a penny. Their output was impressive: The boys could each whip up as many as 1,000 boxes in an afternoon.

Adam left the company after high school but Seth stayed on, working in sales and eventually decorating cakes, though by his own admission he lacked his father’s flair. “I’m just a technician,” he said. “He was the artist.”

In 1992, Seth bought the business outright, though his mother and father continued to work there full time. For decades the elder Mr. Greenberg had been working six days a week — often till midnight on Fridays — and he continued to do so. Seth Greenberg sold the company in 1995, and the family stayed on for another two years until the relationship with the new owners soured.

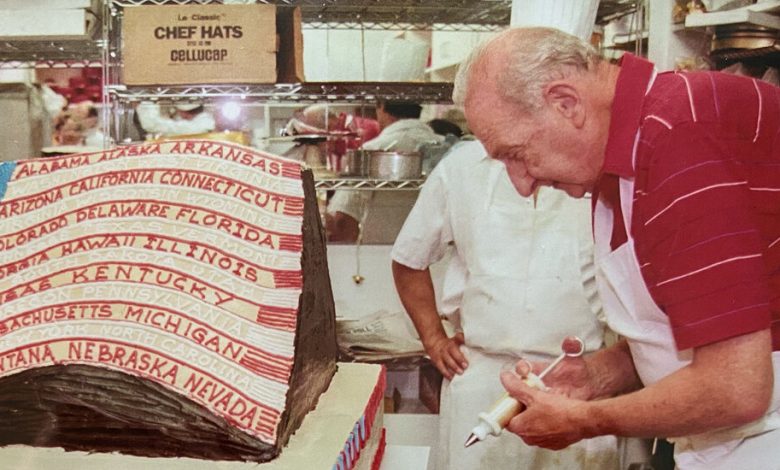

But before the family bowed out for good, they received a call to make a cake for President Bill Clinton’s 50th birthday, in August 1996. They conceived an American flag, made from layers of yellow poundcake. It was a colossus, requiring 432 eggs, 96 pounds of butter, 98 pounds of sugar and 100 pounds of flour, layered with 15 pounds of raspberry preserves and topped with 15 pounds of dark fudge glaze, and it would take two full days to prepare it. (The birthday event was a fund-raiser, and the Greenbergs donated their creation, which would have cost $4,000 at retail.)

The base of the cake was so big, it didn’t fit through the door, requiring some last-minute maneuvering, but there was a bigger problem: The day before the party, Seth, who was studying for his M.B.A. at Columbia Business School, had an exam, a scheduling conflict that turned into a local news event.

“I asked if the White House would send a note,” Seth told The New York Times for an article headlined “A Presidential Cake Is Not a Piece of Cake.” (The paper also printed the recipe.) “They kind of glossed over that.” He said the Democratic National Committee volunteered to help.

Still, Seth had to call his professor, who told him, as he recalled, “You’re taking a hell of a chance that I’m not a Republican.”

On the days leading up to the event, Mr. Greenberg and his son decorated the cake before a swelling crowd, handing out shavings from it as they carved and embellished it to Mr. Greenberg’s exacting standards.