A Companion on the Road to Recovery

By around 2 p.m., just after lunch, activity at the critical care unit of the Jayadeva hospital in Bengaluru, India, is at an ebb. No one is running down the halls with X-rays, bills or samples of body fluids to be tested. The morning rounds are over. The doctors are gone, and the nursing shift has just changed.

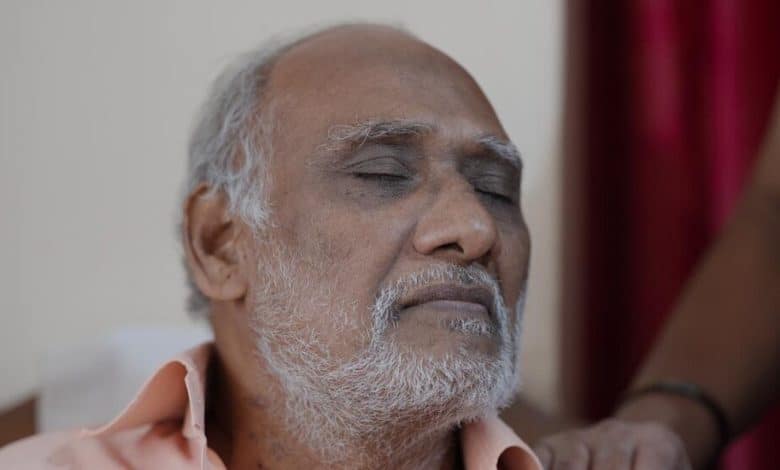

That’s when Girish Balakrishnappa walks in. He is a staff nurse but has the demeanor of a teacher. He starts off by asking everyone to put their phones on silent and gather around. Patients who can walk drag chairs toward him. Those who can’t walk sit up in their beds. Others are asleep, their family members taking notes for them.

Classes with Mr. Balakrishnappa are peppered with jokes and quizzes to keep the listeners close, paying attention and unafraid.

Over the next hour, the nurses, physicians and technicians fall back, ceding the floor to Mr. Balakrishnappa as the ward morphs into an intensive care unit classroom. The students are anxious cardiac care patients, some of whom have only just awakened from open-heart surgery, and their even more anxious families. Mr. Balakrishnappa will tell them how to cough without stressing their hearts, how to scratch without ripping open their wounds and how a pacemaker works.

He will explain that having open-heart surgery does not mean the doctors will remove the heart. In India, where health care walks hand in hand with superstition, myths and luck, Mr. Balakrishnappa helps patients sift through good and bad information — a matter of life and death both inside a critical care ward and after patients are discharged.

This ad hoc classroom is part of a decade-long experiment unfolding in Asia that has been testing a simple yet radical idea: If patients are most comforted by their loved ones, why not involve them in the medical process and see how that affects recovery?