¡Basta de Apagones! The Rot in Puerto Rico Runs Deeper Than Its Disastrous Power Company.

SAN JUAN, P.R. — Hurricane Fiona made landfall on Sunday morning. By 1 p.m. the entire island had been plunged into darkness. Days later, roughly a million homes and businesses in Puerto Rico still lacked power and access to clean water, my own home included. As I sit in a cafe and write, I am overwhelmed by the feeling of déjà vu.

LUMA Energy began supplying power to Puerto Rico after the government privatized what had been a public service in June 2021. It was hired in part to help fix our fragile power grid. But LUMA has not done the job it was contracted to do, including investing in green energy. In the past year, blackouts, sometimes lasting for days, have become a part of our daily life. Even hospitals have been left to rely on generators. Yet, despite the poor service, our electric bills have more than doubled.

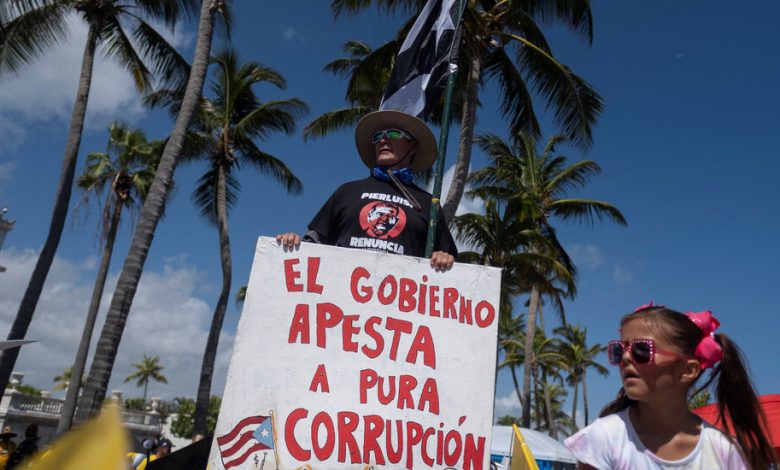

Puerto Rico was unraveling economically and politically long before LUMA and Hurricane Fiona. Austerity programs cut deeply into the public service budget, health care, pensions and education to pay off creditors. Newly elected officials reward party loyalists with government employment, creating a series of sycophants who use public office for their own gain. They award million-dollar contracts to companies that are sometimes owned by party members or relatives, in exchange for kickbacks, or, worse yet, create ghost companies to divert the funds into their own pockets.

As a result, our roads and highways are pockmarked with potholes. While the rest of us struggle to make ends meet, the Senate goes on shopping sprees, spending hundreds of thousands on furniture, laptops and other goods that don’t provide services to taxpayers. While austerity measures closed businesses and schools, Puerto Ricans paid over $15 million covering cases and sentences against officials who violated civil rights.

I was born and raised in Old San Juan. Despite my being a young professional with a master’s degree and a full-time job, an ever-increasing electric bill comes as a shock each month, cutting into potential savings. The dream of owning a home in the city I grew up in, that I call home, feels out of reach because of the high cost of living.

It’s not what I imagined my life would be like.

In the 1950s, new highways supplanted dirt roads for horses and mules. Rows of wooden houses that lacked basic services in the island’s mountainous interior and coastal urban areas were replaced by sprawling concrete developments. Illiteracy declined, families sent their children to universities, and the poverty rate dropped. The Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority, or PREPA, created in 1941, had a hand in powering industrialization and prosperity into the 1970s.

But as industries and people displaced by natural disasters or in search of resources and better-paying jobs left the island en masse, PREPA faced both sharply decreasing revenue and an obligation to provide power for the remaining citizens. The monopoly began skimping on maintenance and borrowed billions of dollars just to stay afloat, accruing $9 billion in debt. In July 2017, PREPA filed for bankruptcy. The decades-long culture of neglect and corruption had left the power grid in shambles, then in September of that year, Hurricane Maria delivered the final blow.

In the wake of an island-wide blackout, PREPA approved a $300 million no-bid contract with Whitefish Energy, based in Montana, to help rebuild Puerto Rico’s electricity grid two months after Hurricane Maria hit. It made little difference that the company had minimal experience with disaster relief and few employees. The deal was later scuttled amid questions about how Whitefish got the job and allegations of price-gouging. In 2018, Gov. Ricardo Rosselló introduced a plan to sell off the power company.

LUMA, a consortium of the Canadian company ATCO and the Houston-based Quanta Services, was contracted to work with PREPA to manage the island’s power last June. It was supposed to cut costs and make desperately needed upgrades to the power grid. Yet despite chronic blackouts, this June I paid $242 for our electric bill, compared with $87 for that month last year. The thing is, the biggest part of LUMA’s fee for running the grid will be paid whether the job is done well or not. There is little accountability for the parties in the agreement.

But there is reason for hope. While Puerto Rico’s Department of Justice, which is responsible for the enforcement of the local law, allows impunity to go unchecked, Washington has begun to pay attention. A 2019 investigation by the United States Department of Justice found that after Hurricane Maria, PREPA employees accepted or demanded bribes to restore power to residences and businesses before serving critical locations like San Juan’s Rio Piedras Medical Center. The power authority also mismanaged a warehouse where materials were stored that should have been available to help restore power on the island. And over six years, more than $300 million in public funds were spent on luxury hotels for consultants related to PREPA.

Last month the former governor Wanda Vázquez was arrested on corruption charges, and at least nine mayors have been accused of corruption. They include Eduardo Cintrón-Suárez, the former mayor of the Municipality of Guayama, who in July was sentenced to 30 months in prison for receiving cash payments in exchange for executing municipal contracts and approving invoice payments for an asphalt and paving company. Many more are believed to be under investigation.

Puerto Ricans shouldn’t have to rely on the U.S. government to deliver justice on a local level. Our own justice system must root out the corruption that threatens to suck the island dry. It can do that by investigating and prosecuting corruption to prove, in part, that the island itself can take the reins of justice. It should demand that the federal government carry out a fiscal restructuring that puts safeguards in place that curb corruption.

Hurricane Fiona was just a Category 1 storm, which is why the scale of destruction has taken so many of us by surprise. We knew things were bad, but we didn’t realize just how agonizingly bad. In the years since Hurricane Maria, our battered infrastructure has only gotten worse. As of Wednesday night, my water service and power were restored. With other storms churning in the Atlantic Ocean, it remains to be seen for how long. At least 20 hospitals are still running on generators.

What is most galling is that it is our own people who rob and abuse us. The betrayal is so insidious that I seethe with anger if I think about it too much. We’re tired of being displaced by wealthy foreigners, who flock to the island to bask on our beaches and get the tax breaks that are not available to us. We’re tired of politicians enriching themselves at our expense. We’re fed up with the blackouts.

After the hurricane passed, my neighbors and I checked on one another. I was moved to tears when my upstairs neighbor told me that our community spirit, the way we look out for one another, is what has helped us survive these past few years. No one is coming to save us. We’ve proved ourselves capable of ousting one governor from office, and we won’t stop until we have created a better, fairer Puerto Rico.

Israel Meléndez Ayala (@IsraelAyala144) is an anthropologist and historian.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.