What Will Ukraine Do With Its New Tanks?

Tens of billions of dollars of weapons have flowed from European and North American countries into Ukraine. Rifles. Bullets. Missiles. Artillery pieces.

At first, those nations insisted that the weapons were “defensive,” designed to help Ukraine fight off a marauding Russian Army that had stormed, unprovoked, across the border.

One year later, as the battered but still potent Russian military prepares for a renewed offensive, the type of weapons heading into Ukraine have changed dramatically. Now, what’s flowing in from the West are armored vehicles, long-range rockets and advanced tanks.

The distinction between offensive and defensive weapons was always a little arbitrary. Now, though, Ukraine will have the ability to play offense and potentially drive Russia out of their country using some of the best weapons in the world. That means the stakes for all sides have increased substantially.

It’s no secret why. After successfully liberating huge areas of southern and northeastern parts of their nation last fall, Ukrainian forces are reportedly planning a new counteroffensive this year. Allied countries are reaching deep into their arsenals to make sure this anticipated counteroffensive has the best possible chance of succeeding.

When, back in February last year, Russian forces crossed into northern Ukraine while also advancing deeper into eastern Ukraine’s Donbas region, the United States and other allies prioritized shipments of ammunition, shoulder-fired anti-tank missiles, air-defense systems and — most importantly — artillery, including hundreds of big guns that are compatible with Western-style shells.

The artillery, perhaps more than any other weapon type, helped Ukrainian troops to defend their capital, Kyiv, and eventually halt Russian advances in the east and south. More than eleven months later, Ukraine has received from its allies no fewer than 750 towed and self-propelled artillery pieces and vehicle-mounted rocket launchers. Another hundred or so are on the way.

“Despite the prominence of anti-tank guided weapons in the public narrative, Ukraine blunted Russia’s attempt to seize Kyiv using massed fires from two artillery brigades,” Mykhaylo Zabrodskyi, Jack Watling, Oleksandr V. Danylyuk and Nick Reynolds wrote in a November study for the Royal United Services Institute in London.

As the Russian assault largely ground to a halt — or even reversed, in places such as Kyiv Oblast — arms transfers to Ukraine began to include more weapons designed for attacking rather than defending. In successive batches starting last spring, Poland donated more than 200 old tanks. Some were ex-Soviet T-72s. Others were locally-made variants of the same Soviet type.

Those tanks were some of the first evidence of a shift to offensive weaponry from foreign nations. That shift accelerated over the summer as the United States and other allies began sending armored personnel carriers — fast-moving, tracked vehicles that transport infantry into battle so they can support the tanks that usually lead any attack. The United States, the Netherlands, Spain, Lithuania, Germany, Australia and other countries donated more than 1,400 of those vehicles, many of them American-designed M-113s.

The armored carriers arrived in time to take part in twin Ukrainian counteroffensives in Kharkiv Oblast and Kherson Oblast — respectively in the northeast and south — starting in late summer. Exploiting gaps in Russian lines, Ukrainian brigades raced deep into occupied territory, cutting Russian supply lines and compelling tens of thousands of Russian troops to retreat.

The counteroffensives liberated thousands of square miles of occupied Ukraine, and set the stage for another potential counteroffensive at some time in 2023. Kyrylo Budanov, head of Ukraine’s military intelligence agency, told ABC News early last month that the Ukrainian military was planning a major attack in the spring. The attack would be aimed at liberating Russian-held territory “from Crimea to the Donbas.” Russian forces, meanwhile, have signaled they might launch their own attacks in order to consolidate their gains and spoil the Ukrainian offensive.

The prospect of clashing offensives has raised the stakes as Ukraine’s allies continue to tweak their donations of weaponry. As new weapons flow in and soldiers become proficient at using them, “we will see the Ukrainians also able to move forward and to change this dynamic on the battlefield,” Laura Cooper, the American deputy assistant secretary of defense for Russia, Ukraine and Eurasia, told reporters last month. “That’s what we’re focused on.”

This new urgency seems to have prompted the United States and other allied countries to begin offering up their surplus infantry fighting vehicles. These vehicles are like armored personnel carriers, but with more offensive armament, including turret-mounted automatic cannons and anti-tank missiles.

With their heavy armament and high speed, infantry fighting vehicles are especially useful for offensive operations. The United States and Germany, respectively, are giving Ukraine M-2 and Marder fighting vehicles. The donations “provide the armor necessary to go on the offensive, to liberate Russian-occupied Ukraine,” Gen. Mark Milley, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, told reporters on Jan. 20, shortly after the Pentagon announced it would donate to Ukraine an initial 109 M-2s.

But the M-2s and similar vehicles were just the start. More and better vehicles soon followed. The United Kingdom pledged 14 of its best Challenger 2 tanks. The United States offered up 31 cutting-edge M-1A2 tanks.

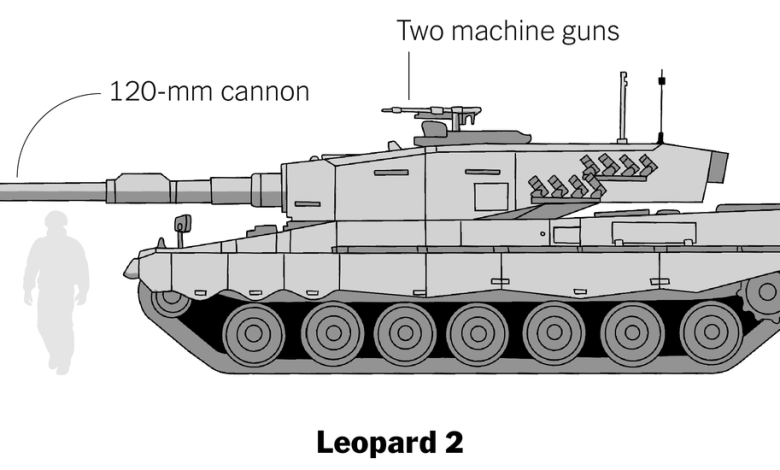

Germany belatedly approved a Polish donation of around a dozen German-made Leopard 2 tanks, signaling to other European countries that they too could do so. Germany then offered Ukraine a dozen or so of its own tanks.

Fast-moving and hard-hitting, tanks are inherently offensive in nature. And the donations of NATO-style tanks, with their sophisticated armor, optics and fire-control systems, represent “an important step on the path to victory,” Volodymyr Zelensky, Ukraine’s president, tweeted.

They’re also the clearest sign yet that the weapons Ukraine’s allies are sending to the war zone are more and more meant for attacking rather than defending. And that suggests some important changes on the battlefield.

David Axe is a staff writer at Forbes and the author of several books, most recently, “Drone War: Vietnam.”

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: [email protected].

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.