When Artists Can’t Go Home, All That’s Left Is Their Art

Pablo Picasso was among the few who stood beside Chaim Soutine’s grave as his corpse was lowered into it. It was Aug. 11, 1943, and Paris was under Nazi occupation. Mr. Soutine — the artist, the genius, the Jew — had died in his hospital bed with his belly cut open after being smuggled into the city in a black-and-white-flagged ambulance to avoid Nazi detection.

Mr. Soutine’s lover had insisted that he procure the best medical treatment available in France, despite the fact that they had been hiding together in the forests and farmland outside Paris so that he would not be rounded up and sent to an extermination camp. The hearse’s journey from farmland to hospital cost him precious hours. By the time the doctor performed the surgery, it was already too late.

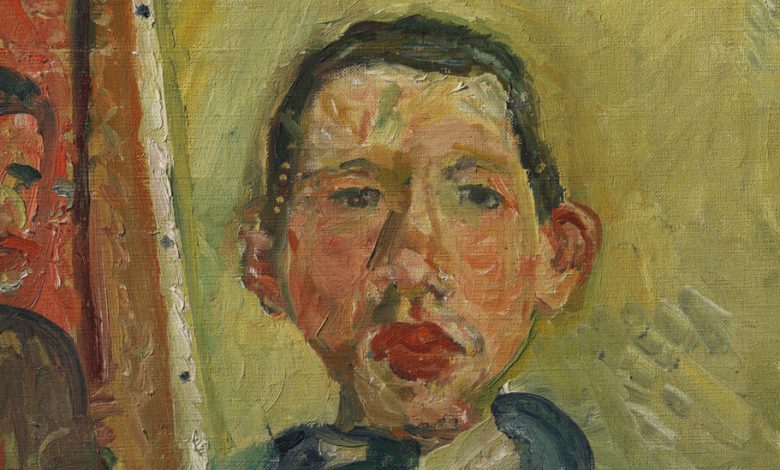

At birth and death, the world assigned Mr. Soutine a status: He was born as a Jew — in a shtetl outside Minsk in what is now Belarus in 1893 — and he died as a Jew. In the 50-year interim he lived only as an artist.

Like many other Ashkenazi Jews, Mr. Soutine left Eastern Europe just after a spate of pogroms that rattled the Russian Empire in the 1910s. After studying painting in Minsk and Vilnius in present-day Lithuania, he joined the school of Jewish painters rankling the French art establishment in Montparnasse. His destitution was well known even in that impoverished milieu, but in the early 1920s an American art dealer bought 52 of his paintings, catapulting him from obscurity into the annals of art history.

In the society of Jewish painters in Paris that he joined in 1913, Mr. Soutine was widely esteemed. He was monomaniacal: utterly, obsessively committed to his craft. “Soutine had no biography outside his art; one might even say that his art was a substitute for a biography,” one art critic wrote. On his deathbed, Amedeo Modigliani whispered to a dealer he and Mr. Soutine had worked with, “I leave you a genius. I leave you Chaim Soutine.”

Perhaps Mr. Soutine would have been surprised to hear that Picasso helped bury him (the two men shared friends but were not friends with each other), but I like to imagine I give his bones a greater shock when I say Kaddish, the Jewish mourning prayer, over his grave every time I visit its corner in Montparnasse Cemetery. Of the traditions he was bequeathed — the Jewish faith, Russian Jewish cultural heritage, the culture refugee communities cultivate in a cosmopolitan center — the only one he seized with both hands was the tradition of great artists in whose company he condignly placed himself. What does identity matter when one has been blessed with genius?