Although public polling on immigration shows a strong shift to the left, survey responses in that vein mask a far more complicated reality. Over and over again, immigration has proved to be politically problematic for Democrats. As far back as 2007, when he was chairman of the House Democratic Caucus, Rahm Emanuel warned that immigration had become the new “third rail of American politics.”

Mary C. Waters, a sociologist at Harvard whose work focuses “on the integration of immigrants and their children, the transition to adulthood for the children of immigrants, intergroup relations, and the measurement and meaning of racial and ethnic identity,” concisely described the immigration paradox in an email:

While those “who favor immigration favor a lot of other issues,” Waters continued,

Waters is chairman of the National Academy of Sciences panel on the integration of immigrants into American society. Americans, she points out,

The reality of the politics of immigration stands in contrast to the more positive Gallup findings that the percentage of people describing immigration as a “good thing” grew from 52 to 75 percent from 2001 to 2021, and the percentage describing it as a “bad thing” fell from 31 to 21 percent. Over the past 20 years, the percentage of voters who say immigration should be increased grew from 10 to 33 percent, while the share who said it should be decreased fell from 43 to 31 percent. The percentage saying immigration levels should be left unchanged remained relatively constant over these two decades, ranging from the mid-30s to the low 40s.

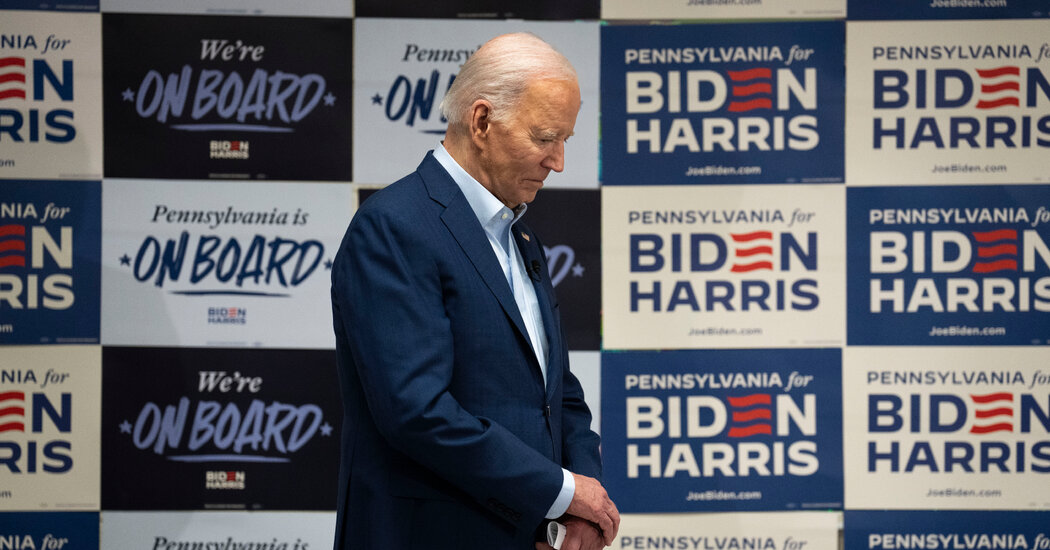

Despite these ostensible leftward trends, however, there is no question that immigration has become a worsening problem for President Biden, and that surging illegal border crossings are weighing down his administration. “A record 1.7 million migrants from around the world, many of them fleeing pandemic-ravaged countries, were encountered trying to enter the United States illegally in the last 12 months, capping a year of chaos at the southern border,” two of my Times colleagues, Eileen Sullivan and Miriam Jordan, reported on Oct. 22.

The percentage of adults who disapprove of Biden’s handling of immigration grew from 39 percent when he took office to 59 percent in late September, according to YouGov tracking surveys. The disappointing showing of Democrats up and down the ticket on Tuesday, in Virginia, in Pennsylvania judicial races and in the closer-than-expected New Jersey governor’s race collectively signal substantial problems for Democrats going forward.

The predicament immigration poses goes well beyond politics. Roger Waldinger, a professor of sociology at U.C.L.A., described the broader implications in an email:

As the Gallup world poll has repeatedly shown, Waldinger continued, “a very large share of the world’s population has an interest in migrating abroad,” especially to countries “where migration yields a very significant payoff.”

The incentives are not limited to economics:

All of these factors, Waldinger added, “are compounded by the effects of climate change and the political insecurities that are driving displacement worldwide.”

These forces, in turn, work to the advantage of the political right, Waldinger continued, and “unfortunately for the left, I don’t see how it can altogether avoid immigration.”

Waldinger notes that

At the same time, Waldinger argues, there is a hidden

The United States, more than any other nation, cannot avoid the conflicts and disputes provoked by immigration. This country is not only has the most immigrants of any country in the world, it is also the first-choice destination of most potential immigrants and, possibly most confounding, it has become inextricably dependent on foreign-born workers to perform essential tasks.

The federal Bureau of Labor Statistics published data in the May 2021 bulletin establishing that

The bureau reported that significantly higher percentages of foreign born than native born workers are employed in health care, food preparation, farming, construction and extraction occupations.

A Nov. 12, 2019 headline in the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel captured the situation succinctly: “Wisconsin’s dairy industry would collapse without the work of Latino immigrants — many of them undocumented.”

Evidence of the dependence on immigrant workers became glaringly apparent during the Covid pandemic.

An April 2020 study “Immigrant Workers: Vital to the U.S. Covid-19 Response, Disproportionately Vulnerable” released by the Migration Policy Institute stated that

A separate December 2020 study, “Immigrant Essential Workers are Crucial to America’s Covid-19 Recovery,” put together by the pro-immigrant group, Fwd.us, showed that

René D. Flores, a professor of sociology at the University of Chicago who studies American attitudes toward immigration, offered some further insights. In response to my inquiry, Flores wrote by email that in survey and focus group research, he and his colleagues have observed that “just mentioning the term ‘immigrants’ is a negative prime among U.S. individuals. It leads them to express more restrictionist views.”

Compounding the problem for pro-immigration Democrats, Flores wrote, is that “exposing U.S. individuals to positive messages about immigration has no effect on their policy attitudes” because when “individuals read negative messages on immigrants, they become motivated to express restrictionist views, particularly conservative and low-educated individuals.”

Democrats, Flores said, carry “a bigger burden” in the debate over immigration:

In a recently presented paper, “The American Immigration Disagreement: How Whites’ Diverse Perceptions of Immigrants Shape their Attitudes,” Flores and Ariel Azar, a graduate student in sociology at the University of Chicago, found that white attitudes toward immigrants could be broken up into “five main classes or ‘immigrant archetypes’ that come to whites’ minds when they respond to questions about immigrants in surveys.”

The authors, describing in broad outline the various images of immigrants held by whites, gave the five archetypes names: “the undocumented Latino man” (38 percent), the “poor, nonwhite immigrant” (18.5 percent), the “high status worker” (17 percent), the “documented Latina worker” (15 percent) and the “rainbow undocumented immigrant” (12 percent).

Two groups elicit the highest levels of opposition to immigration, the authors write:

The authors identify the survey respondents who are most resistant to immigration:

A forthcoming paper in the Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, “Intervening in Anti-Immigrant Sentiments: The Causal Effects of Factual Information on Attitudes Toward Immigration,” by Maria Abascal, Tiffany J. Huang and Van C. Tran, sociologists at N.Y.U., the University of Pennsylvania and CUNY, reveals an additional hurdle facing pro-immigration Democrats.

The authors conducted a survey in which they explicitly provided information rebutting negative stereotypes of immigrants’ impact on crime, tax burdens and employment. They found that respondents in many cases shifted their views of immigrants from more negative to more positive assessments.

But shifts in a liberal direction on policies were short-lived, at best: “In sum,” Abascal, Huang and Tran wrote, the effects of the stereotype-challenging information “on beliefs about immigration are more durable than the effects on immigration policy preferences, which themselves decay rapidly. These findings recommend caution when deploying factual information to change attitudes toward immigration policy.”

The conservative shift to the right on immigration policy raises another question. The Republican Party was once the party of big business and the party that supported immigration as a source of cheap labor. What happened to turn it into the anti- immigration party?

Margaret E. Peters, a political scientist at U.C.L.A. and the author of the 2017 book, “Trading Barriers: Immigration and the Remaking of Globalization,” argues that corporate America’s need for cheap labor had been falling before the advent of Trump, and that that decline opened to door for Republican politicians to campaign on anti-immigrant themes.

In a March 2020 paper, “Integration and Disintegration: Trade and Labor Market Integration,” Peters succinctly describes the process:

On the other side of the aisle, Democrats, in the view of Douglas Massey, a sociologist at Princeton, have failed to counter Republican opposition to immigration with an aggressive assertion of the historical narrative of the United States

Unfortunately, Massey continued,

Ryan Enos, a professor of government at Harvard, has a different perspective. He argues that

This consensus, Enos contends, still holds, but it is fragile:

As Democrats have continued to struggle to reach agreement on major infrastructure and social spending bills, they have been forced to rapidly shift gears on tax hikes without fully addressing potentially unintended consequences. Party members remain tentative, at best, in their willingness to challenge the Senate filibuster rule, and senior House Democrats are retiring in an early warning signal that the party may face severe losses in November 2022.

There are potentially tragic consequences if the Democratic Party proves unable to prevent anti-immigration forces from returning to take over the debate, consequences described by U.C.L.A.’s Waldinger:

Put differently, Waldinger continued, “the ever-greater embeddedness of the unauthorized population increases the legitimacy of their claims.”

In other words, for all intents and purposes, most undocumented immigrants — and perhaps especially the Dreamers — are Americans deserving of full citizenship. But these Americans are on the political chopping block, dependent on a weakened Democratic Party to protect them from a renewal of the savagery an intensely motivated Republican Party has on its agenda.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.