Last November, on the Saturday after Thanksgiving, the second- or third-best player on the third- or fourth-best team in the sixth- or seventh-best conference in women’s college volleyball took the court in Las Vegas. She was the center of attention — not only for the 300 people in the stands but for countless others as well.

Listen to this article, read by Robert Petkoff

Blaire Fleming, a senior, was a starter for the San Jose State University Spartans. For most of her college career, she had been a good but unremarkable, and unremarked-upon, player. Fleming was one of the roughly 6,000 players talented enough to compete in N.C.A.A. Division I women’s volleyball, but she was largely indistinguishable within that cohort. She didn’t play for a powerhouse school like Penn State or Nebraska; she had never received all-conference, much less All-America, honors. In the assessment of Lee Feinswog, a veteran volleyball journalist who writes the 900 Square Feet newsletter, she was “a middle-of-the-pack player.”

Then, suddenly, she was much more than that. A few months before Fleming’s senior season, Reduxx, a “pro-woman, pro-child-safeguarding” online magazine, published an article claiming that Fleming was “a feminine male” — in other words, that she was a transgender woman. Reduxx reported that it had found old Facebook photographs of Fleming in which she appears to be a boy, as well as an old Facebook comment by Fleming’s grandmother in which she referred to Fleming as her “grandson.” The article also quoted the anonymous mother of an opposing player who watched Fleming compete against her daughter and tipped off the publication that she suspected Fleming was transgender: “He jumped higher and hit harder than any woman on the court.”

Advertisement

SKIP ADVERTISEMENT

Fleming declined to speak with the media throughout the season. But earlier this year, over the course of a series of written exchanges and a Zoom interview, she talked for the first time with a journalist, confirming to me that she is in fact transgender. Coaches and administrators at San Jose State already knew this. So did officials at the N.C.A.A., whose rules during Fleming’s time as a student athlete permitted trans women to compete in most women’s sports, including volleyball, provided they underwent hormone therapy and submitted test results that showed their testosterone remained below a certain level. Many of Fleming’s teammates, and even some of her opponents, were also aware that she was trans. “I wouldn’t really refer to it as an open secret,” one former San Jose State volleyball player, who requested anonymity to discuss team dynamics, told me. “It was just more like an unspoken known.”

But after Reduxx outed her, what was once unspoken became loudly debated — and Fleming, in her fourth and final season, went from being a mostly unknown college volleyball player to an unwilling combatant in the culture war. Five teams boycotted their games against San Jose State, choosing instead to forfeit. As the players on one of those teams, the University of Nevada, Reno, explained in a statement, “We refuse to participate in any match that advances injustice against female athletes.”

The controversy became intensely personal when Brooke Slusser —San Jose State’s co-captain and Fleming’s close friend and roommate— joined a class-action lawsuit by a group of female athletes against the N.C.A.A., arguing that the organization’s transgender-participation policy discriminated against women and therefore violated Title IX, the law banning sex discrimination in federally supported education programs and activities. Slusser also became the lead plaintiff in a separate lawsuit against the California State University System, the Mountain West Conference and San Jose State’s women’s volleyball coach, Todd Kress, as well as two San Jose State administrators, that sought to have Fleming immediately declared ineligible. Melissa Batie-Smoose, the Spartans’ assistant coach, took Slusser’s side and was suspended by the university. She later joined Slusser’s lawsuit.

The boycotts and lawsuits drew the attention of conservative media. OutKick, a sports news website owned by the Fox Corporation, ran more than 50 articles about Fleming and San Jose State over the course of the season. “At this rate there might just not be women’s sports if they keep allowing this to happen,” Slusser said in one of several appearances on Fox News. San Jose State offered little in the way of pushback and refused to confirm or deny that Fleming was trans, citing her privacy rights.

The controversy inevitably found its way into the presidential campaign. Appearing at a Fox News town hall for female voters in October, Donald Trump commented on a video of Fleming spiking a ball into an opponent’s face that had gone viral on social media. “I never saw a ball hit so hard,” he marveled. He promised to ban trans athletes from women’s sports if elected. Protesters began appearing at the games San Jose State did play, chanting “No men in women’s sports!” and carrying signs that declared “SAVE WOMEN’S SPORTS”; a smaller number of counterprotesters soon started showing up wearing “TEAM BLAIRE” T-shirts.

Advertisement

SKIP ADVERTISEMENT

Amid all this, Fleming was playing the best volleyball of her life. As an outside hitter, it was her job to deliver kills — precision spikes that opponents can’t return. It was something she had struggled to do consistently over the course of her career. But now she was spiking the ball with strength and accuracy, averaging 15 kills per match, which placed her in the top 60 in the country by that metric. To Fleming and her supporters, her standout play was a testament not just to her mental fortitude but also to her work ethic. But to Fleming’s critics, her performance was yet more evidence of the unfair physical advantages she enjoyed because she was born biologically male.

By late November, when San Jose State faced off against Colorado State in the championship game of the Mountain West Conference tournament in Las Vegas, Fleming was the most famous — or infamous — college volleyball player in the United States. With Trump now re-elected, she was also on the verge of becoming, quite possibly, one of the last transgender women to play any college sport in the United States.

Fleming during the Mountain West Conference finals in November. A few months later, the N.C.A.A. moved to prohibit trans student athletes from competing in women’s sports.Credit…Preston Gannaway for The New York Times

When Trump entered the White House, he quickly made good on his campaign promise, signing an executive order titled “Keeping Men Out of Women’s Sports.” The executive order prompted the N.C.A.A. to announce in February that it was prohibiting trans student athletes from competing in women’s sports, effective immediately. Some prominent Democrats began to shift on the issue, too. Representative Seth Moulton of Massachusetts announced that he wouldn’t want his daughters “getting run over on a playing field by a male or formerly male athlete,” and Gov. Gavin Newsom of California proclaimed it “deeply unfair” for transgender athletes to participate in women’s sports. Public opinion was on their side: A January New York Times/Ipsos poll found 79 percent of Americans — and 67 percent of Democrats — believed trans athletes should be banned from women’s sports.

But the issue remains both fraught and unresolved, with trans athletes still participating in high school and elite sports, lawsuits multiplying and the Trump administration opening investigations into and withholding funds from colleges and universities — and even a state, Maine — where high-profile cases have drawn attention. The story of the San Jose State volleyball team is a cautionary tale about how a policy vacuum can be filled by an all-out culture war.

Advertisement

SKIP ADVERTISEMENT

In Las Vegas, once the conference championship game began, Colorado State, the Mountain West’s first-place team, took a commanding two-set lead over San Jose State, who owed their presence in the championship game, in large part, to the six of their 12 wins that came by forfeit. It looked like a mismatch. Then, in the third set, the Spartans came to life, digging and blocking and spiking their way back into the game. On set point, Slusser assisted on a kill by Fleming, and the two players shouted in triumph — the only sign of their season-long discord coming when, celebrating with their teammates, they avoided slapping five with each other.

But in the fourth set, Colorado State reasserted its dominance and won the match 3-1, leaving Fleming sprawled on the floor in defeat. She had played the final game of her college career. Slusser and the other Spartans, many of them in tears, headed to the locker room, but Fleming lingered on the court. After congratulating some Colorado State players, she made her way into the crowd of spectators to see her mother, with whom I was sitting.

I told Fleming I was sorry her season was over. She let out a mirthless laugh.

“Don’t be,” she said.

When President Trump signed the executive order directing federal funds to be withdrawn from any school that refuses to ban transgender student athletes from women’s sports, he declared, “The war on women’s sports is over.”

Of course, one person’s war on women’s sports is another person’s movement for trans inclusion. Either way, it’s difficult to pinpoint when, exactly, it all began. Some would say it started in 2007, when the Washington Interscholastic Activities Association (W.I.A.A.) adopted a policy allowing trans students in Washington State to participate in sports programs consistent with their gender identity — the first of its kind in the nation, which soon became a model for other states, including California, Connecticut and Oregon. Others point to 2011, when the N.C.A.A. instituted a new policy that allowed trans female student athletes to compete on a women’s team after completing a year of testosterone-suppression treatment. And others argue that it began in 2016, when the Obama administration’s Justice and Education Departments issued a sweeping directive to schools across the country notifying them that Title IX’s prohibition against sex discrimination protected transgender students too. The administration’s guidance was aimed at allowing transgender students to use bathrooms that align with their gender identity. But it also instructed schools to allow transgender students to participate on athletic teams that correspond with their gender identity.

Advertisement

SKIP ADVERTISEMENT

In 2017, a month after becoming president for the first time, Trump had his Justice and Education Departments rescind the Obama administration’s protections for transgender students. But Trump, who as a candidate in 2016 waved an “LGBTs for Trump” pride flag, did not install his own regulations. For a time, Betsy DeVos, the secretary of education, signaled an interest in devising a federal policy that would allow at least some transgender athletes to play on sports teams that corresponded to their gender identity. “They were trying to come up with a trans athlete policy that would affect K through 12,” says Athena Del Rosario, a trans woman who played women’s soccer at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and whom DeVos and other Trump Education Department officials consulted with on the issue. “At that point the Trump administration was supporting some type of inclusion.”

It was against this backdrop of expanding tolerance that Blaire Fleming came of age. Growing up as an only child in the Virginia suburbs of Washington, she spent most of her time hanging out with girls; they did one another’s hair and makeup and talked about their crushes. “I thought I might be a little gay boy,” Fleming told me. “But as I started to get older and got to know some gay boys, I remember feeling a disconnect. I didn’t feel gay; something felt off.” When Fleming was in eighth grade, she heard the word “transgender” for the first time. “It was a lightbulb moment,” she recalled. “I felt this huge relief and a weight off my shoulders. It made so much sense.” At age 14, with the support of her mother and her stepfather, she worked with a therapist and a doctor and started to socially and medically transition.

Throughout her childhood, Fleming played tennis and soccer and participated in gymnastics, but volleyball was her favorite sport. She joined a coed recreational team when she was about 10 and, during the summers, went to volleyball camps on college campuses. In 2018, during junior year, she joined her public high school’s girls’ team. She said that none of the coaches or other players, all of whom knew that Fleming was transgender, objected. The same went for a local club team she joined.

Fleming soon drew the attention of college recruiters. On the requisite Instagram account and YouTube channel she created to upload her highlights, and in the emails she wrote to coaches, Fleming did not mention that she was trans. It was only when she visited a college that she brought it up — telling the coaches that if it was a problem for the school, then she wouldn’t go there. “Almost every one of those conversations went very well,” Fleming told me. “To my knowledge, no one seemed to think that me being transgender was an issue. If it was, they didn’t indicate that to me.”

Advertisement

SKIP ADVERTISEMENT

Fleming accepted a scholarship offer from Coastal Carolina University in South Carolina and started at the school in the fall of 2020. She did not tell her teammates that she was trans, but she says that early in her time there, her coach informed her that some of them knew — and she didn’t notice them treating her any differently. Nonetheless, by the end of her freshman season, she felt she wasn’t fitting in at the school; like many students during the Covid-19 pandemic, she was also struggling with her mental health. She withdrew from Coastal Carolina and went back home to Virginia. She continued to train with her old club volleyball team, and after more than a year off from school, she decided to give college another shot. In the summer of 2022, she received a volleyball scholarship to San Jose State.

Fleming (second from right) during the finals. Even after some teammates learned that she was trans, “life seemed totally normal,” she says — at least at first.Credit…Preston Gannaway for The New York Times

Fleming said that it was important to her that her new teammates know she was trans. She and Trent Kersten, San Jose State’s volleyball coach at the time, discussed her idea that she write the team a letter before her arrival on campus, telling them that she was trans; but, Fleming told me, “I did not want this to be the first thing that people know or think about when they get to know me.” She and Kersten concluded that she could tell teammates individually once she knew them better.

Shortly after the end of her first volleyball season at San Jose State, Fleming says that Kersten let her know that some of her teammates had approached him to tell him that there was a rumor that Fleming was trans. “He said that these teammates were very supportive and told him that they loved and cared about me,” Fleming recalled. “They said that they didn’t expect me to talk about it if I didn’t want to, but they had wanted to let me know that I was safe.”

Still, she was nervous about how this revelation would affect her relationships with her teammates. She says she needn’t have been. “Life seemed totally normal,” Fleming told me. “I didn’t feel like I needed to address it. People knew, but nothing really changed.”

In the decade after the N.C.A.A. introduced its transgender-participation policy, a handful of deep red states — including Idaho, Alabama and Mississippi — passed trans sports bans, but public criticism of trans female athletes was largely confined to the right-wing fringe. There was little public controversy even after CeCé Telfer, a trans female hurdler for Franklin Pierce University, became the first openly transgender athlete to win an N.C.A.A. title, at the Division II track and field championships in 2019. “It was very much under the radar,” says Brian Hainline, who served as the N.C.A.A.’s chief medical officer from 2013 until last year.

Advertisement

SKIP ADVERTISEMENT

But in the fall of 2021, Lia Thomas, a transgender woman, showed up on the University of Pennsylvania’s women’s swim roster. Thomas had competed on Penn’s men’s swim team the previous three seasons and was transitioning during the year Ivy League sports were canceled because of Covid. Racing against men, Thomas ranked 554th and 65th in the 200- and 500-yard freestyle races; among women, she posted some of the best times in the nation in those two events. Her phenomenal and sudden success in the female category seemed to serve as living proof of the claim, made by opponents of trans inclusion in women’s sports, that trans female athletes retained unfair physical advantages. Calls began to come in — from the parents of some of Thomas’s Penn teammates, from the editor of Swimming World magazine — to prohibit Thomas from competing.

In January 2022, Hainline and other N.C.A.A. officials successfully pushed to revise the organization’s policy to require trans athletes to undergo testosterone testing, with the acceptable levels for each sport determined by either its national or world federation or the International Olympic Committee. Shortly thereafter, U.S.A. Swimming announced more stringent policies, halving the permissible limit for testosterone from under 10 nanomoles per liter to under five nanomoles per liter and requiring that trans athletes meet the new testosterone threshold for 36 months.

U.S.A. Swimming’s new rules would have prohibited Thomas from competing in the N.C.A.A. championships that March. But the N.C.A.A. concluded that implementing the new rules just before the championships would be untenable, and the implementation was delayed until the next season, clearing the way for Thomas to swim. At the championships, she earned three podium finishes, placing eighth in the 100-yard freestyle, fifth in the 200-yard freestyle and first in the 500-yard freestyle, becoming the first openly transgender athlete to win a Division I title in any sport.

The swimmer Lia Thomas, an outlier among trans athletes because of her visibility and elite success, after placing first in the 500-yard freestyle during the N.C.A.A. championships in 2022.Credit…Rich von Biberstein/Icon Sportswire, via Getty Images

“Lia Thomas was the major inflection point,” Hainline says, as the debate about trans athletes moved into the mainstream. Before Thomas’s 2021-22 season, nine states had enacted trans sports bans; today there are 25. Lanae Erickson, a senior vice president at the center-left think tank Third Way, who has conducted extensive public opinion research on the transgender issue, told me: “There wasn’t a focus group that we ran where Lia Thomas’s name — or sometimes just ‘that swimmer’ — didn’t come out of someone’s mouth, and they’d use that example to start all of their conversations about the issue.” This meant that for many people, Thomas, who was something of an outlier among trans athletes — because of the advanced age at which she transitioned, the elite level at which she competed and the tremendous success she enjoyed — became the paradigmatic example of one.

Advertisement

SKIP ADVERTISEMENT

Some athletes stood by Thomas. Brooke Forde, who swam for Stanford University’s team at the time, issued a statement that read, in part: “I believe that treating people with respect and dignity is more important than any trophy or record will ever be, which is why I will not have a problem racing against Lia at N.C.A.A.s this year.” But the controversy also gave rise to a new generation of trans-sports-ban activists.

The most prominent was Riley Gaines, a University of Kentucky swimmer who tied Thomas for fifth place in the 200-yard freestyle at the N.C.A.A. championships. The photo of Gaines standing next to Thomas on the podium, a head shorter than Thomas, with an incredulous look on her face, went viral. Gaines soon followed up with an interview with the conservative website The Daily Wire in which she spoke respectfully of Thomas but blasted the N.C.A.A. for allowing Thomas to compete. “I am in full support of her and full support of her transition and her swimming career and everything like that,” Gaines said, “because there’s no doubt that she works hard, too, but she’s just abiding by the rules that the N.C.A.A. put in place, and that’s the issue.”

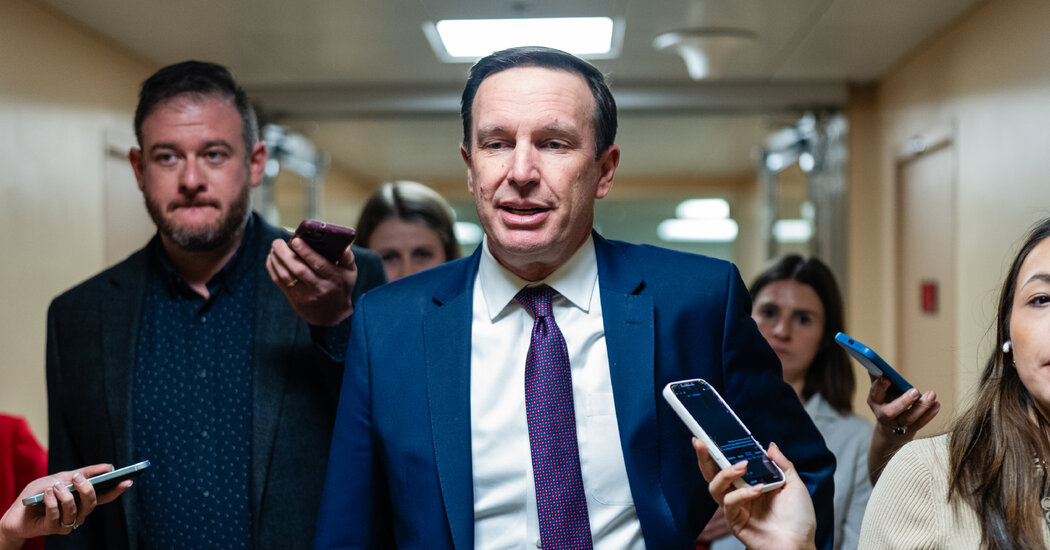

As she continued to speak out against the N.C.A.A. and her media profile rose, Gaines’s rhetoric toward Thomas — and other trans athletes — became more combative. “Lia Thomas is not a brave, courageous woman who EARNED a national title,” she posted on Twitter in March 2023. “He is an arrogant, cheat who STOLE a national title from a hardworking, deserving woman.” Today Gaines is a MAGA activist who focuses on women’s issues; she has both an OutKick podcast, “Gaines for Girls,” and a nonprofit dedicated to combating “gender ideology.” When Trump signed the “Keeping Men Out of Women’s Sports” executive order, he praised Gaines, who was standing over his left shoulder, by name.

Riley Gaines, who rose from University of Kentucky swimmer to conservative political activist, at the signing of the “Keeping Men Out of Women’s Sports” executive order in February.Credit…Andrew Harnick/Getty Images

Well over a decade ago, when the N.C.A.A. and other athletic organizations began making rules for trans participation, the scientific research about transgender athletes was in its infancy. The few scientists who did study the topic generally believed that transgender women who had undergone hormone-suppression therapy were, physiologically, more athletically similar to women than to men. As more data on trans athletes was collected, the scientific thinking seemed to indicate that this was true mainly of transgender women who had undergone hormone-suppression therapy either before puberty or very early in its onset; those who transitioned later and went through male puberty appeared to be, physiologically, more athletically similar to men.

Advertisement

SKIP ADVERTISEMENT

But in recent years, a growing body of evidence has indicated that differences in athletic performance exist between males and females even before puberty. Scientists have also found evidence, in animal models and cultured human cells, for what’s known as the “muscle memory theory.” This theory, as Michael Joyner, a doctor who studies sex differences in human physiology, wrote in a recent article for The Journal of Applied Physiology, posits that “the beneficial effects of high testosterone on skeletal muscle and the response to training are retained even when androgens are absent.” In other words, the physical advantages of having high levels of testosterone are believed to remain long after the testosterone is gone from the body.

All of this has contributed to the concept of “retained male advantage” — the idea that, even after hormone-suppression treatments, and even if those treatments start before puberty, trans athletes are likely to retain physical advantages over those who were born female. “The idea of retained advantage is something that has been postulated for maybe five years,” says Joanna Harper, a leading researcher of trans athletes at Oregon Health & Science University, “and it’s certainly true.”

Some scientists, like Joyner, believe that there is sufficient scientific evidence for retained male advantage to justify prohibiting trans female athletes from competing in elite women’s sports. But the questions that now interest scientists like Harper, who is a trans woman herself, are how those retained advantages manifest themselves, how significant they are in different sports and whether, in certain sports, what Harper calls “meaningful competition” can be preserved despite those retained advantages. “The vast body of evidence suggests that men outperform women, but trans women aren’t men,” Harper says. “And so the question isn’t, do men outperform women? The question is, as a population group, do trans women outperform cis women, and if so, by how much?”

Harper is currently helping to lead an ambitious study of trans adolescents that measures their results on a 10-step fitness test before they start hormone therapy and then, after they have begun to medically transition, every six months for five years. But, she told me when we talked in February, “the current climate makes the study somewhat uncertain.” I assumed she was referring to the Trump administration’s cuts to National Institutes of Health research grants, but she said money was not a problem: The study is being funded by Nike. The problem was Trump’s separate order targeting medical care for transgender youth. “If we can’t perform gender-affirming care,” she explained, “then we can’t bring people into the study.”

In the summer of 2023, Brooke Slusser arrived at San Jose State after transferring from the University of Alabama. She had been an All-American volleyball player in high school in Denton, Texas, and after an unhappy sophomore year at Alabama, she was excited to start over at San Jose State. But first she needed a place to live. Todd Kress, San Jose State’s new volleyball coach, suggested she move in with a group of three players — Brooke Bryant, Alyssa Bjork and Blaire Fleming — who lived together in an off-campus apartment. Kress wanted Slusser, who was a setter, to develop good chemistry with Bryant, Bjork and Fleming, who were among San Jose State’s top front-row players and would depend on Slusser to set them up for spikes.

Advertisement

SKIP ADVERTISEMENT

Slusser immediately hit it off with her new roommates, who called their apartment the Villa, in homage to the reality-TV show “Love Island.” Among the San Jose State volleyball players, the Villa girls were considered to be the most social and most popular. Slusser, who is tall and blond and enjoys going out, felt very much at home.

Not long before the volleyball season started, Slusser recalls, she went out to grab dinner with Bryant and two San Jose State men’s basketball players. They were sitting in Slusser’s car, waiting for their food, when she overheard the two basketball players discussing Fleming. “They were talking about, ‘Blaire,’ ‘man,’ ‘guy,’ all that stuff,” she told me. “And I kind of turned around, and I was like, ‘What are y’all talking about?’” The basketball players told Slusser that they had heard Fleming was transgender. Slusser asked Bryant if she had also heard this about their roommate. Bryant said she had, and Bjork had, too.

Brooke Slusser (center) during the conference finals in November. She joined a lawsuit accusing the N.C.A.A. of violating women’s Title IX rights by permitting trans athletes in women’s competition.Credit…Preston Gannaway for The New York Times

Afterward, Slusser began asking other teammates about Fleming. “They kind of knew little bits and pieces from finding out from other people,” she says. “It was all just kind of like whispers.” The one person with whom Slusser didn’t want to broach the topic was Fleming herself. “You never know what’s true, what’s not, so obviously I didn’t really feel comfortable with this person I just met asking, ‘Hey, is this true?’” she says. “And then if you’re wrong, it’s like, ‘Oh, I’m so sorry.’”

Slusser, who grew up in a conservative household, says she didn’t have any personal objections to Fleming’s being trans. But she says it was an odd situation not having confirmation from Fleming, so she “kind of just honestly brushed it under the rug.” Slusser not only continued to live and party with Fleming in the Villa; she also agreed to be Fleming’s roommate when San Jose State played away games. The four Villa girls, Fleming told me, “became a sort of mini family within the program.” She added, “We were so close that we talked about being bridesmaids in each other’s weddings.”

Advertisement

SKIP ADVERTISEMENT

A few months after the end of that season, on the spring day when Reduxx published its article outing Fleming, Slusser hadn’t looked at her phone before she arrived back home at the Villa. According to Slusser, Bjork and Fleming asked if she could drive them to Chick-fil-A for milkshakes. After hitting the drive-through, they parked to drink them. The car fell silent. Finally, Fleming looked at Bjork and said, “I don’t know how to tell her.” Bjork responded, “Just show her the article.” So Fleming handed Slusser her phone, which had Reduxx pulled up.

Fleming watched as Slusser read the article. When Slusser handed the phone back to her, Fleming said, “Ally already told me that you kind of know a few things, but obviously not everything.”

“Yeah,” Slusser said, “I can assume you know how I feel about it then.”

“You were kind of the one I was most scared to talk to about the situation,” Fleming said.

Slusser says she told Fleming that she believed transgender women shouldn’t be permitted to play women’s sports. Fleming says Slusser made no mention of the sports issue but did tell Fleming that she was worried what her parents and friends back home might think. Both agree that Slusser assured Fleming that her biggest concern at that moment was Fleming’s well-being. “I hope you’re doing OK, because no one deserves this amount of hate on media,” Slusser said. “They don’t know you as a person.” Fleming says that Slusser told her that she still loved her and reiterated that she still wanted Fleming to be one of her bridesmaids. (Slusser does not remember saying she still wanted Fleming to be her bridesmaid.)

A few days later, Kress summoned the volleyball team to a meeting with him, the rest of the coaching staff and a couple of San Jose State administrators. Fleming says she told the group that she was contemplating quitting the team. As she began to cry, some of her teammates tried to comfort her. Though a few of her teammates did have questions about how the team planned to navigate this disclosure, no one, Fleming says, indicated to her that they wanted her to quit. Kress and the administrators assured the players that they were “dealing with it,” Slusser recalls, and they asked that the players not talk to people outside the team, especially reporters, about Fleming. “This is not your story to tell,” one of the administrators told the team. “Blaire is the one going through this.”

Advertisement

SKIP ADVERTISEMENT

That summer, Slusser and Bryant, San Jose State’s co-captains, went to Europe as part of a conference all-star team. There, Slusser says, some of the players from the other Mountain West schools warned them that if Fleming was still on the Spartans’ roster in the fall, their schools might refuse to play San Jose State. When Slusser and Bryant returned to campus, they told Kress about the possibility of boycotts. Kress said he would reach out to his coaching colleagues to take their temperatures. Slusser pressed Kress on what he would do if the coaches told him that they wouldn’t play San Jose State with Fleming still on the team. “There’s a certain point where it’s like, OK, the one person in this scenario that’s causing all this should be removed, and we can play this game,” she told her coach. Slusser says Kress became agitated and the conversation ended. (Kress declined to comment for this article “due to the lawsuit,” he told me in an email.)

It seemed that no one in a position of authority at San Jose State was prepared for what was about to happen — least of all Kress. According to Melissa Batie-Smoose, the associate head coach, Kress told her that he didn’t know San Jose State had a transgender volleyball player on its roster before he took the job in January 2023; when he did find out, soon after both coaches arrived on campus, he didn’t seem terribly pleased.

Kress later wrote in an email, which I obtained through a public records request, to a Reduxx reader who had attacked him for allowing Fleming play for San Jose State: “Maybe you should do your research and discover which Head Coach and coaching staff was here when this SA” — student athlete — “was recruited/brought to SJ.” Kress apparently believed that, if he wanted to keep his job, he had to keep Fleming on the team. “Your issue should be with the NCAA, not me,” he wrote in another email, responding to one of the many critical messages he received about Fleming. “I assume if I removed this SA from the team, you or one of the other haters that have emailed me would pick up my salary. Lol.” Batie-Smoose says Kress agreed with her that, with Fleming, the San Jose State coaches had been “put in a shitty situation.”

The volleyball coach Todd Kress, after a game last October. Although he arrived at San Jose State after Fleming’s recruitment, his personal support for her grew steadily.Credit…Santiago Mejia/San Francisco Chronicle, via Getty Images

One factor that vexes the debate over trans women in female sports is that no one can agree on — or even determine — just how prevalent they actually are. That has led to a range of estimates and conjecture. HeCheated.org, which describes itself as “working to document every instance of men and boys stealing from female athletes in women’s sports,” maintains that, over the last decade or so, at least 585 trans female athletes have competed in women’s sports in the United States. The comedian John Oliver, who has used his HBO show “Last Week Tonight” to advocate for including trans athletes in women’s sports, looked at this same state of affairs and concluded that there are “vanishingly few trans girls competing in high schools anywhere,” essentially declaring it a nonissue.

Advertisement

SKIP ADVERTISEMENT

It is difficult, if not impossible, to arrive at an authoritative number. Consider the seemingly straightforward and presumably answerable question of how many trans athletes were playing college sports in the United States before the N.C.A.A. changed its trans inclusion policy in February. There was one trans female athlete, Sadie Schreiner, a Division III track and field runner at the Rochester Institute of Technology, who was out and another, Fleming, who had been publicly outed. There were also two trans male athletes who were out — a Division II fencer and a Division III runner. But those seem to be the only four who were known to the public. That did not mean, however, that the N.C.A.A. did not know about more.

In December, after Charlie Baker, president of the N.C.A.A., was asked at a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing how many transgender athletes he was “aware of” who were playing N.C.A.A. sports, he answered “less than 10.” He was not asked to specify — and the N.C.A.A. has refused to clarify — how many of those were trans men and how many were trans women. Nonetheless, Baker’s number was significantly smaller than the one given to me a month earlier by Helen Carroll, the former sports project director for the National Center for Lesbian Rights, who helped the N.C.A.A. design its original trans-participation policy and who continues to advise trans athletes. When I asked her in November how many trans athletes were playing in the N.C.A.A., Carroll told me that there were 40 “that the N.C.A.A. knows about.” (There are more than 500,000 athletes competing in N.C.A.A. sports most years.) She wouldn’t speculate about how many trans athletes there were in the N.C.A.A. that the N.C.A.A. didn’t know about, although Joanna Harper, the trans athlete researcher, told me that she was aware of “a few trans athletes who competed entirely in stealth in the N.C.A.A.” and who completed their eligibility before the end of 2024.

It is even more difficult to determine how many transgender athletes are playing sports in high schools and middle schools in the United States. The practice of monitoring the testosterone levels of transgender athletes, outside of elite sports, is uncommon. And it does not appear that any of the 23 states that allow students to participate in sports consistent with their gender identity requires its schools or school districts to report whether they have trans athletes. “We don’t have numbers,” an official with the California Interscholastic Federation, the state’s governing body for high school sports, told me. “We don’t have numbers on white student athletes, Black student athletes or Chinese student athletes, either.”

The only trans student athletes state sports officials do typically know about are those who have become a source of controversy — and typically only when they’re winning. Justin Kesterson, an assistant executive director at the W.I.A.A., recalls preparing for protests at Washington State’s 2023 cross-country championships over a trans female runner from a Seattle high school whom Riley Gaines and others had criticized in conservative media. But the runner from Seattle didn’t make the podium, defusing the planned protests. As it turned out, one runner who did make the podium, a junior from Spokane named Verónica Garcia, was also trans. But the people who had come to protest the Seattle runner were not aware of this, so they didn’t disrupt the awards ceremony. By the following spring, when Garcia won a 400-meter race at the 2024 state track and field championships, the fact that she was trans was no longer unknown, and she was loudly booed.

Advertisement

SKIP ADVERTISEMENT

In September, a few games into the Spartans’ 2024 season, Kim Slusser, Brooke’s mother, followed the @icons_women account on Instagram. The account belongs to the nonprofit group the Independent Council on Women’s Sports, or ICONS, which was founded by Kim Jones and Marshi Smith in 2022 in the wake of the Lia Thomas controversy.

Jones, the mother of a Yale University swimmer who competed against Thomas, says she was inspired to act after watching her daughter endure the “public humiliation” of repeatedly losing to Thomas. She recalls listening to her daughter talk about how, when she and some of her teammates tried to raise questions about the fairness of Thomas’s inclusion, Yale coaches and administrators instructed them to stay quiet, lest they damage the mental health of Thomas and other students. “I had no idea schools could be so effective at bullying female student athletes,” Jones told me. (Yale Athletics did not respond to requests for comment.)

Smith, who was an All-American swimmer at the University of Arizona, says she was “completely devastated” to see Thomas “standing on the same podium where I once stood many years ago” at the N.C.A.A. championships. After Smith wrote an open letter to the N.C.A.A. protesting Thomas’s participation in women’s events that was signed by more than 40 former Arizona swimmers and coaches, she and Jones connected for a phone call to discuss creating what Smith calls an organization with a singular focus on “the right to a sex-based category in sports.”

Three years later, ICONS is the pre-eminent organization in the trans-sports-ban movement. While neither of its founders has a media or political background, they have displayed a remarkable instinct for driving media and political narratives. ICONS has been working with Bill Bock, a lawyer who resigned from the N.C.A.A.’s Division I committee on infractions in protest over the transgender-athlete policy. And in March 2024, with financial backing from ICONS, Bock filed a federal lawsuit against the N.C.A.A. on behalf of Gaines and more than a dozen other female college athletes for having policies that violated their Title IX rights and allowing Thomas to compete at the 2022 national championships.

The complaint describes Gaines as having “no clothes on” and being “mortified” when she encountered Thomas, “a fully grown adult male with full male genitalia,” as Thomas was “undressing in the women’s locker room” at the N.C.A.A. championships. It also offers a base-line defense of “the female category” in sports, which exists, the suit argues, in order “to give women a meaningful opportunity to compete that they would be denied were they required to compete against men.”

Advertisement

SKIP ADVERTISEMENT

According to some women’s sports advocates, allowing trans athletes to compete in the women’s category threatens to render the category meaningless — and to undo all the social progress it has enabled. They believe that, beyond the measures of physiological advantage, the very presence of trans athletes in women’s sports is unfair — that every title or record or scholarship won by a trans athlete essentially deprives a female athlete. Doriane Coleman, a Duke Law School professor who studies sex and gender, and who was a champion runner at Cornell University in the early 1980s, told me, “We worked so hard for this space, and the fact that other people who are not in sports or are not athletes think so little of it that we have to step back and step aside again is just devastating.”

Smith keeps a close eye on ICONS’ social media followers, scrutinizing their profiles and pictures, and she sent Kim Slusser a message after discovering that her daughter played volleyball for San Jose State. “I anticipated that if her mom is seeking to follow us,” Smith says, “that she might have something to say.” Shortly thereafter, Smith, Jones and Riley Gaines met with Brooke Slusser over Zoom. Slusser says they were the first adults she had talked to about the Fleming controversy, besides her parents, who didn’t try to change her opinion. “I remember leaving that meeting just feeling a relief,” she told me, “like I’m not crazy for feeling this way.”

The ICONS leaders didn’t just want to validate Slusser’s feelings. They also wanted to let her know she had options. One of those was joining Gaines’s lawsuit against the N.C.A.A. Smith and Jones connected Slusser with Bock, who drew parallels between Slusser’s situation and Gaines’s. As Bock told me, he considers both Thomas and Fleming to be “narcissistic males that are bringing attention to themselves and taking opportunities from women.” After talking it over with her parents, Slusser decided to sign on to the suit.

On Sept. 23, the night before San Jose State’s Mountain West opener at Fresno State, Slusser asked to meet with Kress and the rest of the coaching staff at the team hotel. She told them she was joining Gaines’s lawsuit. “I just hope you all can respect me on my decision to do something I believe in, in the same way you all respected supporting Blaire,” she said. The next morning, Slusser asked Fleming to come to her hotel room. (Although Slusser and Fleming were still roommates at the Villa, they were no longer sharing a hotel room for away games.) There, she told Fleming she was joining Gaines’s lawsuit. “I felt betrayed and perplexed,” Fleming recalls. “I didn’t understand how she could care about me and do this at the same time.”

The amended complaint, which named Fleming and described her as “a male who identifies as transgender and who claims a female identity” — thereby outing her a second time — was a bombshell. It claimed that in practices Fleming’s spikes traveled “upwards of 80 miles per hour,” faster than Slusser “had ever seen a woman hit a volleyball,” thus putting “everyone on the team at risk of serious injury”; and that when Slusser brought these concerns to Kress, he “brushed Brooke off and would not talk further about it.” (The 80-miles-per-hour claim was later removed from the lawsuit after ESPN analyzed video of five of Fleming’s spikes and found that the fastest was estimated to travel 64 miles per hour and the average was 50.6 miles per hour — on the high end, but still within the normal range for women’s college volleyball.) The filing drew the attention of OutKick, Fox News and Megyn Kelly, the prominent conservative podcast host.

Advertisement

SKIP ADVERTISEMENT

More important, it drew the attention of other Mountain West schools. In a four-page letter to the presidents of the Mountain West universities that play women’s volleyball, Smith and Jones of ICONS noted Slusser’s legal action and demanded that, in order “to protect your women student athletes,” their teams refuse to play San Jose State. A few days later, Boise State University announced that it was forfeiting its game against the Spartans (after its athletic director had a Zoom meeting with Smith), generating more headlines. The University of Wyoming soon did the same. Then Utah State University and the University of Nevada, Reno, forfeited as well. Gaines awarded “medals of courage” and “BOYcott” T-shirts to some of the forfeiting schools’ players, while elected officials in each of the school’s respective states — including Gov. Spencer Cox of Utah, who two years earlier, while vetoing a trans sports ban bill, argued that “rarely has so much fear and anger been directed at so few” — lined up to praise the boycotts.

As the forfeits piled up and San Jose State’s season began to unravel, Melissa Batie-Smoose, the associate head coach, found herself in the awkward position of siding with her team’s — and her boss’s — harshest critics. She and Kress first coached together almost two decades earlier, and when Kress came to San Jose State, Batie-Smoose was his first hire. Over the years, they had helped each other navigate multiple ups and downs — hirings and firings, marriages and divorces. They almost always saw eye to eye. But now they were increasingly at odds.

Melissa Batie-Smoose, then San Jose State’s associate head coach, in October. As a woman with a position of authority in the volleyball program, she had a special responsibility, she felt, to be an advocate for women.Credit…Santiago Mejia/San Francisco Chronicle, via Getty Images

Batie-Smoose had been uncomfortable with Fleming’s presence on the team ever since she learned that Fleming was trans. Some of the discomfort seems to have been personal. “She’s a pain in the ass. He’s a pain in the ass,” Batie-Smoose told me when we discussed Fleming. “Doesn’t do anything you ask. Terrible teammate.” (No one else I spoke to at San Jose State characterized Fleming’s conduct this way.) But Batie-Smoose cast her objections to Fleming in more high-minded terms as well. She believed that, as one of the only women in a position of authority in San Jose State’s volleyball program, she had a special responsibility. “We have a male trainer, we have a male strength coach, we have a male head coach,” she says. “There’s too many men coaches coaching females, so I’m very much a female advocate.” (A spokeswoman for San Jose State said in a statement that the two athletic department officials who supervised volleyball were women.) Batie-Smoose was racked with guilt about the high school players she helped recruit who came to San Jose State unaware that one of their teammates would be trans. Not telling recruits about Fleming, she says, felt like “lying.”

Batie-Smoose says that she voiced these concerns to Kress and that, while he might not have had them at the same “level” that she did, he shared them. So she was disappointed when, in the summer of 2024, Kress essentially dismissed Slusser’s and Bryant’s fears that other teams would refuse to play San Jose State if Fleming remained on the Spartans’ roster. And she was even more disappointed when Kress reacted angrily to Slusser’s decision to join Gaines’s lawsuit — complaining to Batie-Smoose that Slusser was trying to ruin the team’s season. Batie-Smoose defended Slusser to Kress and beseeched him to remove Fleming from the team. “That’s fine if she wants to be a trans,” she says she told Kress, “but she has no business in women’s sports.” Kress wasn’t moved. “It always flipped back to protecting Blaire,” Batie-Smoose says of her conversations with Kress, which were growing more and more heated. “It would always go back to, ‘How do you think Blaire feels?’”

Advertisement

SKIP ADVERTISEMENT

Indeed, Slusser’s joining Gaines’s lawsuit seemed to bring Kress closer to Fleming. No longer a problem he inherited, she was now a player about whom he cared deeply. “They were always on the phone, and he was always checking in on her,” Randilyn Reeves, another San Jose State volleyball player, recalls. Fleming appreciated the support, alerting her coach when she received hateful or threatening messages (which was often) and venting her frustrations and fears to him. “He was so empathetic,” she told me. “He tried very hard to be there for me.”

When Kress wasn’t worrying about Fleming, he was worrying that San Jose State’s entire season might be canceled. In emails to four of his fellow Mountain West coaches that I obtained through a public records request, Kress asked them not to forfeit their games against his team. “Everyone has played against her the last two years,” Kress wrote, of Fleming. “So I guess the election-year situation is what’s pushing this agenda currently. Not sure.”

San Diego State University’s coach, Brent Hilliard, replied that his team would not forfeit its matches against San Jose State. “We have known about this situation for over two years now,” Hilliard wrote, “so not a whole lot has changed with us.” When San Jose State and San Diego State did play, one of Fleming’s spikes appeared to hit a San Diego State defender in the face — producing the viral video that many opponents of trans athletes, including Trump, denounced. But the San Diego State player, Keira Herron, told me she had no problems with the play or with Fleming. “It was fine, I was fine, the ball didn’t hurt,” she said. “Everyone gets hit in volleyball. It comes with the game, man.”

But continuing to play was a mixed blessing for the Spartans, as the tensions inside the team and on the coaching staff only grew worse. According to Batie-Smoose, players started skipping practice, saying they needed mental-health breaks, so the team was almost constantly short-handed; the players who did show up sometimes got into yelling matches with one another, with practices devolving into what Kress described to one person as a “bitch fest.”

Slusser says Kress essentially stopped speaking to her, passing his instructions through Batie-Smoose. But that arrangement eventually fell apart when Kress and Batie-Smoose stopped speaking to each other. Kress’s personal support for Fleming seemed to evolve into a broader embrace of all trans athletes. After one game, he read a prepared statement to reporters in which he described himself as “an advocate for Title IX” but also “an advocate for humanity, an advocate for social justice.” He believed, he continued, that “the two can exist at the same time.”

Advertisement

SKIP ADVERTISEMENT

Batie-Smoose, meanwhile, began working with ICONS and, in late October, filed a Title IX complaint against Kress and San Jose State, requesting an investigation into what she said was their overt favoritism toward Fleming at the expense of the other players. A few days later, Batie-Smoose was walking into San Jose State’s volleyball facility to prepare to coach a game against the University of New Mexico when she was met by administrators, who told her that she was suspended indefinitely and barred from campus, effective immediately. (Through a spokeswoman, San Jose State did not offer an explanation for Batie-Smoose’s suspension but said it expects all its employees to abide by “our standards, policies and applicable laws regarding student and employee privacy.”) The team was told of Batie-Smoose’s suspension 10 minutes before game time. Batie-Smoose’s place in the program was taken, numerically at least, by an armed policeman, who began traveling with the volleyball team for their protection.

The season took a toll on all of San Jose State’s players and coaches, but Fleming told me it was almost unbearable for her. After Slusser joined Gaines’s lawsuit, Fleming found herself being frozen out by other team members as well. Eventually, one of the only teammates who remained her close friend — the player who would be her hitting partner at practice and sit with her on the team bus or at team meals — was Reeves, who had transferred into the program that year. “If I was in her shoes, I would need someone,” Reeves told me, “so I just wanted to be that person for her.” Fleming eventually moved out of the Villa into a studio apartment. She says she cried almost every night and considered quitting multiple times during the season. At one point, she told me, she “felt suicidal.” It was, she wrote, “the darkest time in my life.”

Fleming in November at the final game of her college volleyball career. “Do I think I’m the last?” she says, referring to trans female athletes in women’s sports. “No.”Credit…Preston Gannaway for The New York Times

It’s tempting to wonder if Fleming somehow might have been spared all this misery. What if Reduxx had never outed her? What if Slusser had never joined Gaines’s suit? Or what if politicians had been willing to make difficult policy interventions that might have defused the situation before it erupted?

It seemed for a time as if Joe Biden was prepared to do just that. During the 2020 campaign, he promised to put a “quick end” to Trump-era policies that rolled back transgender rights. And then in 2022, on the 50th anniversary of the passage of Title IX, Biden’s Education Department proposed new rules that extended Title IX protections to transgender students — a return to the Obama-era interpretation.

Advertisement

SKIP ADVERTISEMENT

But according to a number of former Biden-administration officials, there remained a simmering debate inside the administration about whether those Title IX protections should extend to sports. On one side were Susan Rice, the director of the White House’s Domestic Policy Council, and Catherine Lhamon, the Education Department’s assistant secretary for civil rights; Lhamon had the same role during the Obama administration and was heavily involved in the original expansion of Title IX protections. Rice and Lhamon maintained that there was no legal difference between letting trans students use bathrooms that align with their gender identity and letting trans student athletes play on sports teams that align with their gender identity.

On the other side were administration officials who believed that the competitive, zero-sum nature of sports made them different from bathrooms — that some transgender athletes would enjoy unfair physical advantages over women. Most important, one of the officials holding this view was Biden himself. “The president was particularly focused on the competition issue,” says one former Biden administration official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to publicly discuss the matter.

The two sides ultimately arrived at a compromise. Biden’s Education Department would propose a new rule that specifically addressed transgender student athletes and sports. On the one hand, the proposed rule would prohibit outright bans on transgender athletes; on the other hand, it would allow schools to “limit or deny” the participation of trans athletes if the schools could demonstrate that their inclusion would harm “educational objectives” like fair competition and player safety. This would result, Biden-administration officials hoped, in a nuanced system in which, at the lower rungs of school sports, where participation rather than competition was the focus, transgender student athletes would be able to play on teams that align with their gender identities. But at the upper echelons where scholarships and championships were at stake — as in Division I volleyball — transgender athletes might not be able to play if schools determined that their participation would risk unfair competition or injury.

The Biden administration apparently didn’t want to delve any deeper into the transgender debate ahead of the 2022 midterms, so it delayed releasing the proposed rule until April 2023. Activists on both sides of the issue immediately savaged it — those on the right for not instituting an outright ban and those on the left for not mandating inclusion of all trans student athletes. The rule-making process drew more than 150,000 comments. But rather than aggressively defend the proposal, the Biden administration stayed largely silent. “It was just left to wither on the vine,” says Third Way’s Lanae Erickson. Last December, after the election and a month before Trump’s inauguration, it withdrew the proposed rule altogether.

Following Biden’s exit from the presidential race last July, Kamala Harris seemed willing to address the trans-athlete issue. According to three people familiar with Harris’s campaign strategy, the campaign expected that the moderators would ask Harris about transgender children in sports during her September debate with Trump. The answer Harris’s advisers prepared for her, according to a person familiar with her campaign strategy, emphasized that trans children should be made to feel welcome in their schools but also acknowledged the concerns of parents whose kids, especially older ones, play competitive sports and want to make sure the competition is fair. But no one ever asked her, and the candidate didn’t bring it up on her own.

Advertisement

SKIP ADVERTISEMENT

Even before the N.C.A.A. rescinded its transgender-inclusion policy in the wake of Trump’s “Keeping Men Out of Women’s Sports” executive order, the era of trans women participating in Division I sports had most likely come to an end. What happened at San Jose State all but guaranteed that.

Last year, Sadie Schreiner, the trans woman runner at the Rochester Institute of Technology, put her name into the N.C.A.A. transfer portal. After placing third in the 200 meters at the N.C.A.A. Division III championships, she was hoping to run at a Division I school. Her times drew the interest of Division I coaches — and some, like those at Towson University in Maryland, remained interested even after she told them that she was trans. Schreiner took a recruiting visit there. “I met everyone, and things looked as they should for a potential athlete,” she says. She was ready to commit. But then, in the middle of the controversy surrounding Fleming and in the wake of the election, Schreiner received a phone call from one of the Towson coaches with some bad news. “It was something along the lines of, ‘Our administration has decided that we can’t provide a safe enough environment for you in this political climate,’” Schreiner recalls. No school wanted to be the next San Jose State.

Schreiner consoled herself in the knowledge that she could still run for R.I.T. in Division III — until, in February, the N.C.A.A. banned all trans athletes, and her college career was brought to an abrupt end. After the Lia Thomas controversy, there were some people inside the N.C.A.A. who argued that the organization should bar transgender athletes from participating in Division I sports but allow them to participate in Division III, whose schools do not offer athletic scholarships. This would create what Brian Hainline, the N.C.A.A.’s former chief medical officer, calls “a continuum system” that allowed for “flexibility at the nonelite level.”

But at the moment, such a system — one that recognizes the inherent tension between fairness and inclusion, that acknowledges both the benefits of participation and the zero-sum nature of competition — is no longer a possibility. In its place, we have a fractious, seemingly irresolvable culture war,